|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Jan 28, 2020 7:48:15 GMT -5

“That was the end of the Lincoln County war, proper. Murphy had died, a broken man, and crownless monarch, and the rest were ready to throw down their guns and call it a draw. All except the Kid and his immediate followers. But from that point, Billy’s career was not that of an avenger, fighting a blood-feud. He reverted to his earlier days and became simply a gunman and an outlaw, subsisting by cattle-rustling . . . Meanwhile the Kid went his ways, rustling cattle and horses. One Joe Bernstein, clerk at the Mescalero agency, made the mistake of arguing with the Kid over some horses Billy was about to drive off. A Jew can be very offensive in dispute. Billy shot him down in cold blood, remarking casually that the fellow was only a Jew.” —Robert E. Howard to H.P. Lovecraft, February 1931 After the Lincoln County War, Billy the Kid return to cattle rustling and horse stealing to make a living, but was still warring over the murder of John Tunstall. One year after the war, however, Jimmy Dolan and Billy Bonney made their peace and agreed to stop fighting. This didn't last long. Billy had a plan to obtain a pardon from the new governor - Lew Wallace, the Civil War general and author of Ben Hur. Needless to say, this didn't go so well either. Listen to the next installment of Black Barrel Media's series on Billy the Kid titled, "On the Run" here: infamousamerica.libsyn.com/billy-the-kid-on-the-run |

|

efb

Wanderer

Posts: 11

|

Post by efb on Jan 28, 2020 11:41:38 GMT -5

"Bill Longley had just shot his first man, and started on the red trail which led to the foot of the gallows." (The Wandering Years)

William Preston (Bill) Longley (1851-78) was hanged for murder in Giddings, TX. He's buried there in the city cemetery under a state historical marker.

He claimed to have killed 32 men, but recent research by Rick Miller (Bloody Bill Longley: The Mythology of a Gunfighter) concluded that the real number probably was six at most, all unarmed or taken by surprise, and one may have been a woman. Miller's excellent biography questions the traditional story that Bill was driven to a life of gunplay by the upheavals of Reconstruction in Texas. More likely, he was a hot-tempered alcoholic who used the tribulations of Reconstruction as an excuse for his bad behavior. Regardless, the romantic myth was the one that REH would have known and embraced. Had he ever gotten around to writing at length about Bill, the result would probably have been similar to Louis L'Amour's portrait in The First Fast Gun (1959), with maybe a dash of Rory Calhoun's standard-issue Western good-guy version in the old TV series The Texan.

|

|

|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Jan 28, 2020 19:09:42 GMT -5

"Bill Longley had just shot his first man, and started on the red trail which led to the foot of the gallows." ( The Wandering Years) William Preston (Bill) Longley (1851-78) was hanged for murder in Giddings, TX. He's buried there in the city cemetery under a state historical marker. He claimed to have killed 32 men, but recent research by Rick Miller ( Bloody Bill Longley: The Mythology of a Gunfighter) concluded that the real number probably was six at most, all unarmed or taken by surprise, and one may have been a woman. Miller's excellent biography questions the traditional story that Bill was driven to a life of gunplay by the upheavals of Reconstruction in Texas. More likely, he was a hot-tempered alcoholic who used the tribulations of Reconstruction as an excuse for his bad behavior. Regardless, the romantic myth was the one that REH would have known and embraced. Had he ever gotten around to writing at length about Bill, the result would probably have been similar to Louis L'Amour's portrait in The First Fast Gun (1959), with maybe a dash of Rory Calhoun's standard-issue Western good-guy version in the old TV series The Texan. That was great! Thanks for sharing that. I recently wrote a piece for REHupa that compared Howard and Louis L'Amour, and you would be amazed at how similar their life stories are, as well as their writing. There are so many things, but both of them were into boxing, both loved poetry, and both wrote for the pulps (L'Amour started in them, writing for some of the same ones Howard had written for). I conclude with what others have said before me: that Howard was developing a Western (Texas) personality toward the end of his life, which most likely signified a shift in what he was writing and, had he lived, he may have had the stardom that L'Amour has. And saying that, let me also say, I love L'Amour's stories, and currently only have 5 of his novels left to read. |

|

|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Jan 28, 2020 19:16:28 GMT -5

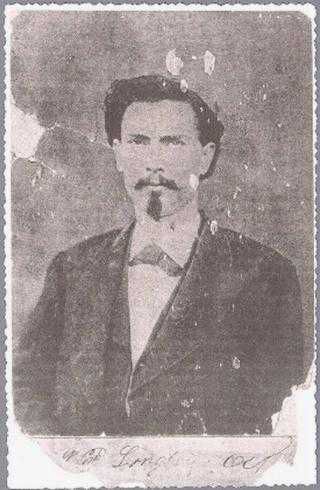

#/media/File:WilliamPrestonLongley.jpg)  Bill Longley Bill Longley Born on Mill Creek in Austin County, Texas, October 6, 1851 and was hung on October 11, 1878 in Giddings, Texas. |

|

|

|

Post by charleshelm on Jan 28, 2020 20:00:50 GMT -5

Thanks, charleshelm, for uploading the pictures of the book. This is the perfect place for them - it is a very Howardesque book. My pleasure. Lots more cool pictures in it. |

|

|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Jan 29, 2020 8:00:09 GMT -5

“When Pat Garrett went after Billy the Kid, he had a posse, its true. But he asked no man to do his shooting. With his own hand he killed Tom O’Phalliard, Charlie Bowdre and Billy himself, breaking up, practically single-handed, the most desperate band of outlaws that ever haunted the hills of the Southwest.” —Robert E. Howard to H.P. Lovecraft, September 22, 1932 “Pat Garrett, who killed Billy the Kid was a hunter of a later day, and helped exterminate the remnants of the great herds in the Texas Panhandle.” —Robert E. Howard to H.P. Lovecraft, March 6, 1933 “And Pat Garrett, who ended the blazing comet-trail that was the life of the Billy the Kid. Garrett was an Alabama man, but he grew to manhood in Texas.” —Robert E. Howard to H.P. Lovecraft, January 1931 There's a new sheriff in town and his name is Pat Garrett. Once Governor Lew Wallace placed a price on Billy the Kid's head, the posse was formed and Garrett was on the hunt, attempting to lure Billy into a trap. The penultimate episode of Black Barrel Media's series on Billy the Kid tells this story in the chapter "Billy the Kid: Wanted Dead or Alive." Link to the episode here: infamousamerica.libsyn.com/billy-the-kid-wanted-dead-or-alive |

|

|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Jan 30, 2020 8:09:25 GMT -5

“We rounded a crook in the meandering street and it burst upon us like the impact of a physical blow. There was no mistaking it. We did not - at least I did not - need the sight of the sign upon it to identify it. I had seen its picture - how many times I do not know. I do not know how many times, and in what myriad different ways and occasions I have heard the tale of Billy’s escape. It is the most often repeated, the most dramatic of all the tales of Southwestern folk-lore. When you hear a story long enough and often enough, it becomes like a legend. Yet I will not say that the sight of that old house was like meeting a legend face to face; there was nothing fabulous or legendary about the actuality. The realism was too potent, too indisputable to admit any feeling of mythology. If the Kid himself had stepped out of that old house, it would not have surprized me at all.” —Robert E. Howard to H.P. Lovecraft, July 1935 “The Kid was twenty-one when he was killed, and he had killed twenty-one white men. He was left handed and used, mainly, a forty-one caliber Colt double action six shooter, though he was a crack shot with a rifle, too. That he was a cold blooded murderer there is no doubt, but he was loyal to his friends, honest in his way, truthful, possessed of a refinement in thought and conversation rare even in these days, and no man ever lived who was braver than he. He belonged in an older, wilder age of blood-feud and rapine and war. Yet to compare him with such brigands as Jesse James, Sam Mason, the Harpes, etc., is foolish. The Kid was an aristocrat among his kind, and as far above torture, needless brutality and senseless slaughter as any man might be.” —Robert E. Howard to H.P. Lovecraft, February 1931 In both of the quotes above, Howard talks about the legend of Billy the Kid - the first sparked by recounting his visit, the latter by his abilities with a gun. The last episode of Black Barrel Media's series on Billy the Kid talks about "The Legend" and, like Howard, describes the incredible escape from jail he made before finally meeting his end at the hands of Pat Garrett. Link to the final episode, "The Legend," here: infamousamerica.libsyn.com/billy-the-kid-the-legend |

|

|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Jan 31, 2020 8:29:17 GMT -5

Here is an edited passage (limited to discussion on Billy) that Howard wrote to Derleth about Billy the Kid, the left-handed shooter: “I have often wondered what would have been the result of an encounter between Jack Hayes and John Wesley Hardin, or Billy the Kid, or Wild Bill Hickok. I’m inclined to believe that each would have killed the other. I’m assuming, of course, that it would have been a fair fight. Actually, it probably wouldn’t have been. “The skill of a gunman consisted almost as much of getting the drop on the other fellow as it did in drawing and shooting. I believe Billy the Kid was just a flashing fraction of a second quicker on the draw than any of the others mentioned, but I’m not sure. . . “Billy the Kid died on his feet, with his gun in his hand, but blinded by the darkness that masked his killer . . . “The Kid was as slick as Hardin, but he had the advantage of mechanics; double-action guns had come in, in his time, and he used one of that sort – a .41, worn high up on his left hip, as he was left-handed . . . “What Billy accomplished in a single movement, or at most a slight change in a single movement, Hardin was forced to do with three – Billy simply rolled the gun and pulled the trigger as he reversed it, while Hardin had to draw back the hammer and release it as he rolled the pistol . . . “Again, when Billy the Kid killed Joe Grant, they were standing face to face. Hearing that Grant was after him, the Kid feigned ignorance of the cowpuncher’s motive, complimented his ivory-handled pistol, and lifting it out of his scabbard, pretended to examine it – but in reality turned the cylinder so the hammer would fall on an empty chamber. Grant was too drunk – and too stupid – to notice the Kid’s action. The Kid handed the gun back to Grant – Grant stuck it in his face and pulled the trigger – the hammer snapped futily, and the Kid laughed in his face and killed him.” —Robert E. Howard to August Derleth, December 29, 1932 |

|

|

|

Post by charleshelm on Jan 31, 2020 20:17:43 GMT -5

Of course now, with the transfer bar safety, you may choose to carry with a loaded chamber under the hammer, although the manufacturers discourage it.

As the saying goes, if you find yourself in a fair fight your tactics suck.

|

|

|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Feb 1, 2020 9:13:12 GMT -5

There is no quote for this posting as this "Billy the Kid Museum" in Hico, Texas, came after Howard's death. So, what if Howard and everyone else was wrong? What if Billy the Kid was not, in fact, killed by Pat Garrett on July 14, 1881? What if he escaped to Texas and settled in Hico, a town not too far of a drive east of Cross Plains? And what if he did live the rest of his life there as "Brushy" Bill Roberts? This is, of course, a highly Texan story, or perhaps one of those Texas Tall Tales that Howard became fond of after learning about Pecos Bill, and doing him one up with his own Breckinridge Elkins. Around 1950, Brushy Bill claimed he was the legendary Billy the Kid, and he had been living in Hico, Texas, all the years in-between. It is a fascinating story, and even more interesting museum in Hico. Learn more about the Billy the Kid Museum in the following video: |

|

|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Feb 3, 2020 8:28:40 GMT -5

“There is no part of the United States whose history is more obscure, so little known, as that of Texas. We have always been more or less isolated from the rest of the nation, and life has been such a terrific struggle for existence that the arts and literature had no opportunity to develop. It is only in the last few years that native Texans are beginning to write the chronicle of the Southwest. Much of it is already lost and forgotten. Much will never be written. I myself know of incidents that would make vivid and dramatic reading; but I have not written of them, and I do not intend to.” —Robert E. Howard to August Derleth, March 1933 When Howard and Derleth wrote to each other, much of their time was spent discussing the weather, geography, and history of their respective regions. In the March of 1933 letter to Derleth, Howard discusses that because Texas was on the frontier within living memory of its current residents, much of its history was as yet unrecorded. It was only during Howard's lifetime that people began developing literature related to Texas, thus capturing the culture and history of the state. J. Frank Dobie (1888-1964), the Texas folklorist, is generally considered the grand-daddy of them all. Howard knew this history would make for "vivid and dramatic reading," which is why he spent so much time beginning to develop what Rusty Burke has called his "Texas personae" and why he had talked about writing a book one day called: "An Unborn Empire." Yet, again, he says that he will probably not write it, but little did he know, in his preserved letters, he already was. |

|

|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Feb 4, 2020 8:29:45 GMT -5

“I should have told you that I meant you to keep the copy of “Frontier’s Generation”. I have several other copies. If you like it, you are more than welcome to it. … “I hope you’ll like Clyde’s book. One objection I have heard voiced to works of this kind – dealing with Texas – is the amount of gore spilled across the pages. It can not be otherwise. In order to write a realistic and true history of any part of the Southwest, one must narrate such things, even at the risk of monotony. … “Authentic history or realistic fiction of Texas must be gory. Writing fiction with the purpose of selling it, I would trim it down, past the facts, lest I be looked on as a mere sensationalist. Write a fiction book with half a dozen killings in it, and the critics would brand it melodramatic and impossible. Yet such an absolutely authentic work as Charles Siringo’s autobiography contains repeated references to murders and homicides. And in John Wesley Hardin’s autobiography, or rather in that part of it covering his life from his birth, in 1853, to the time he went to prison in 1878, descriptions are made of, or references to, the killings of 66 men. More than half of these were killed by Hardin himself. Nor was this super-homicide limited to the lower strata of life, as in other localities. If that were the case, history would not need to be so detailed about it; but the wealthy ranchman was as likely to be shot out of his saddle as the most humble vaquero. The politician wore his guns under his coat-tails just as regularly as did the cattle-rustler." —Robert E. Howard to August Derleth, March 1933 If Robert E. Howard had ever written his history of early Texas, which he tentatively titled "An Unborn Empire," the passage above regarding the "gore spilled across the pages" and the fact "it can not be otherwise," assuredly would have been part of his introduction to the book. Texas history, whether detailing the early violence from the Comanches to the Texas Revolution, or in Howard's times with the last remnants of being a frontier or the violence caused by Prohibition, Texas has a history of being gory. Howard could very well have written the book and become, like Harold Lamb, an author who wrote both historical fiction, as well as biographical histories that are exciting to read. |

|

|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Feb 5, 2020 8:19:59 GMT -5

Charlie Siringo Charlie Siringo(February 7, 1855 – October 18, 1928) “Yet such an absolutely authentic work as Charles Siringo’s autobiography contains repeated references to murders and homicides.” —Robert E. Howard to August Derleth, March 1933 In the last post, the quote from Howard mentioned Charlie Siringo (repeated above). Siringo was a Texan, born in Matagorda. While his autobiography does not show up on Robert E. Howard’s bookshelf of known books, he does seem to be familiar with Siringo’s autobiography A Texas Cow Boy, Or, Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony (1885). In this thoroughly entertaining autobiography, Siringo details his life on the many cattle drives heading north out of Texas. The book was widely popular when it was published and, not long after, Siringo moved to Chicago and took up working with the Pinkerton Security Agency. In 1912, he authored another autobiography on his time as a private detective titled, A Cowboy Detective: A True Story of Twenty-Two Years with a World Famous Detective Agency (1912). This is also makes for interesting reading. Siringo just so happens to have been in places throughout his life where major events were taking place and he became involved, including participating in the posse hunting down Billy the Kid, witnessing the Chicago Haymarket Riots first hand, and infiltrating Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch. As my students would say, Charlie Siringo was a "bad-ass." As both books are in the public domain, you can find them on the Internet Archive. Link to them here: archive.org/details/texascowboyorfif00siri/mode/2uparchive.org/details/cowboydetectivet00siririch/mode/2up |

|

|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Feb 6, 2020 8:13:35 GMT -5

"Texas feuds were short and bloody. They did not, as in Kentucky, drag on through the generations. The Sutton-Taylor, and the Lee-Peacock feuds were probably the most famous." —Robert E. Howard to August Derleth, March 1933 Since I have been pulling on the March 1933 letter from Robert E. Howard to August Derleth, I thought I would continue posting on that same letter. Whenever Howard wrote to Lovecraft or Derleth, within one letter, he would regale them with many stories of Texas history and lore. In this one, after talking about Texas gore and mentioning Charlie Siringo's autobiography, Howard began talking about Texas feuds, similar to those made famous in Kentucky. He mentions the Sutton-Taylor feud as the first of two of the most famous. The feud began in March of 1868 as a law enforcement encounter that turned personal. It was really William E. Sutton and friends versus the Taylor family, so, not quite like two full families warring with each other. William E. Sutton was a deputy sheriff in Clinton, Texas, and the conflict was with the Taylor family which included Pitkin Taylor and Creed Taylor, a member of the post-Reconstruction Texas State Police Force. The Taylors also brought in their own friends, included John Wesley Hardin (pictured above). The feud continued until December 1876, when the Texas Rangers finally put a stop to the feud. Due to the Texas Ranger connection, the Texas Ranger Museum in Waco, Texas (an excellent museum to visit), recently opened an exhibit about the feud. Here is a Discovering the Legend video that addresses the Sutton-Taylor feud, as well as the new exhibit: |

|

|

|

Post by linefacedscrivener on Feb 7, 2020 8:35:54 GMT -5

Bob Lee Bob Lee “Texas feuds were short and bloody. They did not, as in Kentucky, drag on through the generations. The Sutton-Taylor, and the Lee-Peacock feuds were probably the most famous – the latter the more obscure because it was fought in the thickets and river bottoms of eastern Texas. It lasted from 1867 to 1871, during which time more men were killed than in the whole course of the famous Hatfield-McCoy feud of Kentucky. (Incidently, one of my best friends in this town is a Kentucky man, and close kin of the McCoys; if all that family were the fighters he is, I don’t see how the Hatfields ever licked them.)" —Robert E. Howard to August Derleth, March 1933 Howard is right. The lesser known, but certainly more violent of the family feuds in Texas is the Lee-Peacock feud. This took place not long after the Civil War at the four corners of four counties located north of Dallas (Fannin, Grayson, Collin, and Hunt). The feud was really a four year continuation of the Civil War. Bob Lee (pictured above) had joined the Confederacy, but before he even returned home, he learned that Lewis Peacock had set up a Union sympathizer group in his own hometown. Tensions ensued until late in 1866, when Lewis Peacock and his followers kidnapped Bobby Lee and made him sign a promissory note for $2000 to gain his release. He signed to get away and the war was on. Over the next four years, it is estimated that as many as 50 people were killed in the feud. In part because there are no significant documentaries on this feud, but mainly because I am a big fan of Old Time Radio and just listened to this episode of Suspense, I thought I would suggest a half-hour of entertainment from the best OTR show ever created. Listen to "The Hunting of Bobby Lee" here: www.oldtimeradiodownloads.com/thriller/suspense/hunting-of-bob-lee-1951-10-29 |

|