|

|

Post by emerald on Jun 1, 2024 16:04:37 GMT -5

Picked up, "Ironclad" with James Purfoy and Paul Giamatti on DVD. What am I in for? I watched it a long time ago, I remember being annoyed by the camera shake in the action scenes, but the movie is solid 6; its dirty and bloody, and Purefoy is excellent, as always. Agreed. This is a good movie with a couple of great scenes. There's a bit where Purefoy busts out of concealment to ride to the assistance of his besieged friends that's as Howardian as hell. Also, one of the very few times you'll see a morning star mace put to use in a movie. |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Jun 1, 2024 18:29:25 GMT -5

I watched it a long time ago, I remember being annoyed by the camera shake in the action scenes, but the movie is solid 6; its dirty and bloody, and Purefoy is excellent, as always. Agreed. This is a good movie with a couple of great scenes. There's a bit where Purefoy busts out of concealment to ride to the assistance of his besieged friends that's as Howardian as hell. Also, one of the very few times you'll see a morning star mace put to use in a movie. Seen a couple of clips on YouTube, looks good. Also, found the full movie on YouTube: Ironclad 2011 |

|

|

|

Post by kemp on Jun 1, 2024 19:34:41 GMT -5

Thinking on it, but not really sure how Knights defending Rochester Castle from the tyrant King John has anything to do with the warriors of the steppe, maybe this should be moved to another thread, or we can always create 'Warriors of the British Isles in movies, music and art'  Having said that I watched this one years ago, very enjoyable, might watch it again so thanks for the link, especially the tie in to the Magna Carta which was about restoring the rights of the English lost after the Norman invasion, but that's another story for a different thread. |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Jun 1, 2024 23:37:26 GMT -5

...something a little more relevant to the Warriors of the Steppe: Keanu Reeves is Genghis Khan's Ultimate Weapon in BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B

SUMMARY SUMMARY

BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B takes fans back to the 13th century, giving a deeper look into B's life serving Genghis Khan.

Boom Studios reunites Reeves, Kindt, and Garney for a brutal showdown between B and Genghis Khan.

Historical realism adds depth to the brutal world of BRZRKR, making The Lost Book of B essential reading for fans.

Keanu Reeves’ BRZRKR returns as Genghis Khan’s ultimate weapon in the new BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B. Reeves’ soon to be iconic character is one of the most exciting comic book debuts of the past decade, shattering sales records and defying expectations. Since its conclusion, publisher Boom Studios has released special books fleshing out the BRZRKR universe, and The Lost Book of B takes fans back to the 13th century.

Boom Studios unveiled more information about BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B on their website. The book will reunite the original BRZRKR creative team of Reeves, writer Matt Kindt and artist Ron Garney. In the 13th century, B (the book’s hero) is in the employ of the notorious warlord Genghis Khan. One of Khan’s premiere soldiers, B has racked up numerous kills and victories. Yet now, B is beginning to question his loyalties, leading to a showdown of historical proportions. The book will feature a cover by Garney as well as variants by Bill Sienkiewicz and David Nakayama. The book will feature a cover by Garney as well as variants by Bill Sienkiewicz and David Nakayama.

The Lost Book of B promises to be the bloodiest BRZRKR title yet. Genghis Khan was a real person, a bloodthirsty tyrant who ruled much of the known world. B was crucial to his success, but Lost Book of B looks at what happens when B questions Khan. Khan will no doubt be angry with B, which will lead to a showdown between them. Inserting historical figures into B’s story adds a layer of realism, and drives home just how long Keanu Reeves’ barbarian character has been alive. BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B will be essential reading for fans.

Source: Boom Studios

BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B is on sale August 21 from Boom Studios! |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Jun 16, 2024 7:12:23 GMT -5

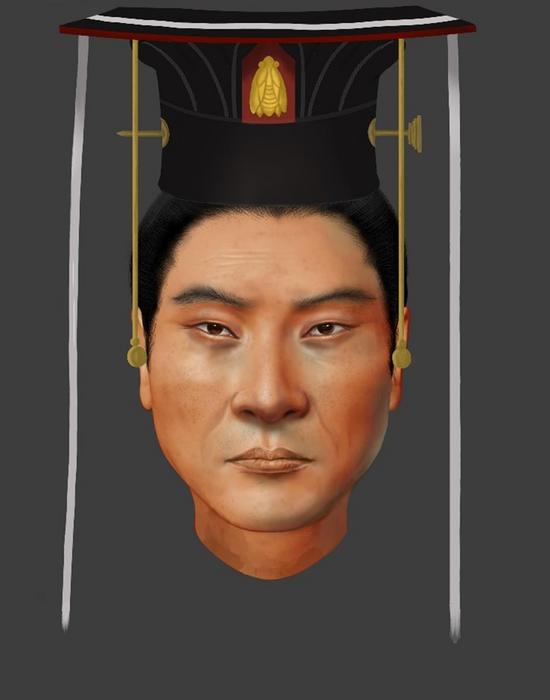

Ancient DNA reveals the appearance of a 6th century Chinese emperor THE FACIAL RECONSTRUCTION OF EMPEROR WU WHO WAS ETHNICALLY XIANBEI What did an ancient Chinese emperor from 1,500 years ago look like? A team of researchers reconstructed the face of Chinese Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou using DNA extracted from his remains. The study, published March 28 in the journal Current Biology, suggests the emperor’s death at the age of 36 might be linked to a stroke. It also sheds light on the origin and migration patterns of a nomadic empire that once ruled parts of northeastern Asia.Emperor Wu was a ruler of the Northern Zhou dynasty in ancient China. Under his reign from AD 560 to AD 578, Emperor Wu built a strong military and unified the northern part of ancient China after defeating the Northern Qi dynasty.Emperor Wu was ethnically Xianbei, an ancient nomadic group that lived in what is today Mongolia and northern and northeastern China.“Some scholars said the Xianbei had ‘exotic’ looks, such as thick beard, high nose bridge, and yellow hair,” says Shaoqing Wen, one of the paper’s corresponding authors at Fudan University in Shanghai. “Our analysis shows Emperor Wu had typical East or Northeast Asian facial characteristics,” he adds.In 1996, archaeologists discovered Emperor Wu’s tomb in northwestern China, where they found his bones, including a nearly complete skull. With the development of ancient DNA research in recent years, Wen and his team managed to recover over 1 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on his DNA, some of which contained information about the color of Emperor Wu’s skin and hair. Combined with Emperor Wu’s skull, the team reconstructed his face in 3D. The result shows Emperor Wu had brown eyes, black hair, and dark to intermediate skin, and his facial features were similar to those of present-day Northern and Eastern Asians.“Our work brought historical figures to life,” says Pianpian Wei, the paper’s co-corresponding author at Fudan University. “Previously, people had to rely on historical records or murals to picture what ancient people looked like. We are able to reveal the appearance of the Xianbei people directly.”Emperor Wu died at the age of 36, and his son also died at a young age with no clear reason. Some archaeologists say Emperor Wu died of illness, while others argue the emperor was poisoned by his rivals. By analyzing Emperor Wu’s DNA, researchers found that the emperor was at an increased risk for stroke, which might have contributed to his death. The finding aligns with historical records that described the emperor as having aphasia, drooping eyelids, and an abnormal gait—potential symptoms of a stroke.The genetic analysis shows the Xianbei people intermarried with ethnically Han Chinese when they migrated southward into northern China. “This is an important piece of information for understanding how ancient people spread in Eurasia and how they integrated with local people,” Wen says.Next, the team plans to study the people who lived in ancient Chang’an city in northwestern China by studying their ancient DNA. Chang’an was the capital city of many Chinese empires over thousands of years and the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, an important Eurasian trade network from the second century BC until the 15th century. The researchers hope that the DNA analysis can reveal more information about how people migrated and exchanged cultures in ancient China.Source: www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/1038341The emperor Wu's wife was the daughter of the 3rd Türk (Göktürk) Kaghan Muqan (553 – 572AD), her name was Empress Ashina. They recently found out that she is also of North East Asian (97,7%) ancestry:

Source: www.researchgate.net/publication/366965287_Ancient_Genome_of_Empress_Ashina_reveals_the_Northeast_Asian_origin_of_Gokturk_Khanate

|

|

|

|

Post by hun on Jun 21, 2024 14:03:34 GMT -5

I'm pretty certain I posted this publication on this thread before, but can't seem to find it:  Christopher I. Beckwith, The Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to China, Princeton University Press, 2023DESCRIPTION:A rich, discovery-filled history that tells how a forgotten empire transformed the ancient worldIn the late 8th and early 7th centuries BCE, Scythian warriors conquered and unified most of the vast Eurasian continent, creating an innovative empire that would give birth to the age of philosophy and the Classical age across the ancient world―in the West, the Near East, India, and China. Mobile horse herders who lived with their cats in wheeled felt tents, the Scythians made stunning contributions to world civilization―from capital cities and strikingly elegant dress to political organization and the world-changing ideas of Buddha, Zoroaster, and Laotzu―Scythians all. In The Scythian Empire, Christopher I. Beckwith presents a major new history of a fascinating but often forgotten empire that changed the course of history.At its height, the Scythian Empire stretched west from Mongolia and ancient northeast China to northwest Iran and the Danube River, and in Central Asia reached as far south as the Arabian Sea. The Scythians also ruled Media and Chao, crucial frontier states of ancient Iran and China. By ruling over and marrying the local peoples, the Scythians created new cultures that were creole Scythian in their speech, dress, weaponry, and feudal socio-political structure. As they spread their language, ideas, and culture across the ancient world, the Scythians laid the foundations for the very first Persian, Indian, and Chinese empires.Filled with fresh discoveries, The Scythian Empire presents a remarkable new vision of a little-known but incredibly important empire and its peoples. Christopher I. Beckwith, The Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to China, Princeton University Press, 2023DESCRIPTION:A rich, discovery-filled history that tells how a forgotten empire transformed the ancient worldIn the late 8th and early 7th centuries BCE, Scythian warriors conquered and unified most of the vast Eurasian continent, creating an innovative empire that would give birth to the age of philosophy and the Classical age across the ancient world―in the West, the Near East, India, and China. Mobile horse herders who lived with their cats in wheeled felt tents, the Scythians made stunning contributions to world civilization―from capital cities and strikingly elegant dress to political organization and the world-changing ideas of Buddha, Zoroaster, and Laotzu―Scythians all. In The Scythian Empire, Christopher I. Beckwith presents a major new history of a fascinating but often forgotten empire that changed the course of history.At its height, the Scythian Empire stretched west from Mongolia and ancient northeast China to northwest Iran and the Danube River, and in Central Asia reached as far south as the Arabian Sea. The Scythians also ruled Media and Chao, crucial frontier states of ancient Iran and China. By ruling over and marrying the local peoples, the Scythians created new cultures that were creole Scythian in their speech, dress, weaponry, and feudal socio-political structure. As they spread their language, ideas, and culture across the ancient world, the Scythians laid the foundations for the very first Persian, Indian, and Chinese empires.Filled with fresh discoveries, The Scythian Empire presents a remarkable new vision of a little-known but incredibly important empire and its peoples.Amazon Links: www.amazon.co.uk/Scythian-Empire-Central-Eurasia-Classical/dp/0691240531www.amazon.com/Scythian-Empire-Central-Eurasia-Classical/dp/0691240531 |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Jun 23, 2024 2:44:58 GMT -5

Here's a review of Beckwith's Scythian book:  Christopher Beckwith likes to shake up the staid world of archeologists, philologists and historians with big claims. In his Empires of the Silk Road, he argued the debt of world civilization to unfamiliar peoples from inner Asia, changing a Euro-centric or Sino-Centric approach to history into steppe-centricity. The Scythian Empire takes this one step forward by attributing many of the contributions from the steppe to a single people, the Scythians. In Beckwith’s telling, the Wusun, the Xiongnu, the Yuezhi, the Tokharians and the Soghdians are all Scythians, as are the Medes.This is a big, simplifying explanation, which, if widely accepted, would make the heretofore complicated history of Central Asia a lot more accessible. What is unsure is how many readers will be convinced by Beckwith’s arguments.The very title of the book is sure to provoke. The prevailing view of the Scythians (Masters of the Steppe, Pankova, Simpson, 2021) is that they did not organize themselves into a recognizable empire. The first people to have mastered mounted combat, the pastoralist Scythians migrated, during the first millennium BCE into the territories of settled peoples, including the Assyrians, the Chinese and the Mauryas in India. Acting as mercenaries, tribal auxiliaries and occasionally as warlords, they spread their culture from the Yellow River to the Danube, leaving behind in tumulus graves their characteristic three-bladed arrows, horse sacrifices, and magnificent gold jewelry, now the pride of museums like the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg. Their intangible legacy included the adoption of cavalry by the major empires of Eurasia. Modern survivors of their original stock include the Ossetes in the northern Caucasus and probably the Pashtuns of the Hindu Kush. Christopher Beckwith likes to shake up the staid world of archeologists, philologists and historians with big claims. In his Empires of the Silk Road, he argued the debt of world civilization to unfamiliar peoples from inner Asia, changing a Euro-centric or Sino-Centric approach to history into steppe-centricity. The Scythian Empire takes this one step forward by attributing many of the contributions from the steppe to a single people, the Scythians. In Beckwith’s telling, the Wusun, the Xiongnu, the Yuezhi, the Tokharians and the Soghdians are all Scythians, as are the Medes.This is a big, simplifying explanation, which, if widely accepted, would make the heretofore complicated history of Central Asia a lot more accessible. What is unsure is how many readers will be convinced by Beckwith’s arguments.The very title of the book is sure to provoke. The prevailing view of the Scythians (Masters of the Steppe, Pankova, Simpson, 2021) is that they did not organize themselves into a recognizable empire. The first people to have mastered mounted combat, the pastoralist Scythians migrated, during the first millennium BCE into the territories of settled peoples, including the Assyrians, the Chinese and the Mauryas in India. Acting as mercenaries, tribal auxiliaries and occasionally as warlords, they spread their culture from the Yellow River to the Danube, leaving behind in tumulus graves their characteristic three-bladed arrows, horse sacrifices, and magnificent gold jewelry, now the pride of museums like the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg. Their intangible legacy included the adoption of cavalry by the major empires of Eurasia. Modern survivors of their original stock include the Ossetes in the northern Caucasus and probably the Pashtuns of the Hindu Kush.

Beckwith sees both the impact and the legacy of the Scythians on a far bigger scale. For him the Scythians are the founders of the Median and Persian empire, of the Zhao kingdom in China’s Warring States era, and ultimately the Qin dynasty of China’s first emperor. In his telling, the Scythian raiders in the Middle East are identical to the Medes who served as allies of the Assyrians and then supplanted them. Depictions of Medes and Scythians in Assyrian and Persian bas-reliefs indeed suggest a close affinity. Cyrus the Persian and Darius are both Medic-Scythians. Darius’s monotheism arises from steppe Tengrism (belief in a sky God), whose prophet Zoroaster writes in a language we call Avestan, but is actually Scythian. The boldness of these assertions takes one’s breath away, while at the same time providing explanations for many previously murky turns in Herodotus’s narrative of Persian history.

Turning to China, Beckwith is no less bold. King Zhao Wuding, who proclaimed the necessity of “dress like the barbarians and shooting from horseback (胡服骑射)”, is not a Han Chinese with a radical program of cultural appropriation, but rather a Scythian prince Sinicized by later Chinese historians. Zheng, the future Shi Huangdi, grew up as a hostage in the Zhao court, but he too is shown as a Scythian, which is why his cavalry ultimately prevailed to end the Warring States period and create the Chinese empire. Even the name for China itself, 華 (huá), reflects Scythian “Arya”, “noble”. The great steppe empire of the Xiongnu is also seen as a Scythian polity, with ethnic intermixtures of Turkic, Mongolic or Tungusic elements.

While many of Beckwith’s arguments are plausible, if not ultimately provable, he tests his readers’ acquiescence when he argues that the Buddha and Laozi were Scythians, together with Zoroaster and the Greek Anacharsis. All were noted figures in the great period of intellectual ferment between 500 and 100 BCE, dubbed the Axial Age by Karl Japers. The German philosopher could not account for the mysterious synchronicity of this ferment across Greece, India and China. Beckwith’s explanation is that the wide-ranging Scythians invented philosophy. This reviewer pumps for the explanation of Eric Havelock (Preface to Plato, Harvard, 1963), who argued that philosophy resulted from wide-spread literacy, itself the product of increasing exchange and social specialization. Did this happen as a result of the Scythian trading and empire building? That is entirely plausible.

Crucial to Beckwith’s sweeping narrative is the assumption that the Scythians maintained their identity over centuries and throughout their migrations. He claims that the Scythians conquered other nations and “creolized” them, without defining what this means. Other instances of migration and conquest suggest that identities can be fluid. The Russians are named for a Swedish tribe, the English and the French for German tribes. The steppe Magyars managed to impose their language in Hungary, the Turkic Bulgars adopted the Slavic language of their subjects. The Tatars of Russia started off as Shamanistic Mongolian-speakers and wound up as Muslim Turkish speakers. It is problematic to say that an ancient Persian or Zhao person identified as a Scythian.

Beckwith will have none of this. He argues that the tradition of divine kingship and the royal tribe, as defined by the Scythians, kept a hold on the peoples of the steppe, such that later successors of the Scythians, the Xiongnu, the Turks and even the Mongols, could only imagine having a ruler of the seed of the royal tribe (cf The Horde). Beckwith argues extensively for the persistence of this notion in the identity of many steppe dynasties, along with the associated term “Arya”, meaning noble.

Beckwith displays a mastery of philology and epigraphy across a number of languages, including old Chinese and old Tibetan, cuneiform inscriptions and Greek manuscripts. He insists on reexamining the interpretation of ancient texts, since the received translations may lead us astray. As an example, he points out that a scribal error in Herodotus had historians looking for the “Colaxai” people, when “Scolaxai” were intended, a dialect variant of the name Scythian. The edition conveniently replicates all the ancient text for students and scholars to make their own judgements.

The significance and persistence of the Scythians’ impact on history should not be underestimated. Their contribution to the founding of the first empires in the Middle East, India and China is hard to dispute. Did they actually rule over the Persian and the Chinese empires themselves? Beckwith’s readers will be torn between the attraction of his big, simplifying theory, and the stretch of imagination that full acceptance of his arguments require.Words by David Chaffetz Source: asianreviewofbooks.com/content/the-scythian-empire-central-eurasia-and-the-birth-of-the-classical-age-from-persia-to-china-by-christopher-i-beckwith/ |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Jun 30, 2024 1:32:54 GMT -5

Another documentary from the Khan's Den Youtube channel, this time on the Karakhans of Central Asia:

The Karakhanids: First Turkic Muslim Empire

Description:

This documentary explores the pivotal role of the Kara-Khanid Empire in shaping Central Asian and Islamic history. From the dominance of Turkic dynasties across the Eurasian Steppe to the rise of the Kara-Khanids, we trace the evolution of Turkic political power and cultural influence.

The narrative begins with an overview of major Turkic empires, including the Xiongnu, Göktürks, Uyghurs, and Kyrgyz, highlighting the unique supremacy of the Göktürks.

We then examine the factors leading to the fragmentation of Turkic political unity and the subsequent emergence of diverse, independent Turkic states adopting various religious and cultural identities.

Central to our story is the formation of the Kara-Khanid Khaganate in 840 CE, born from the alliance of Karluk tribes. We delve into the significance of the Kara-Khanids' conversion to Islam, marking a crucial turning point in the integration of Turkic peoples into the broader Islamic world.

The documentary covers key aspects of Kara-Khanid history, including:

- Origins and tribal composition

- Territorial conquests and expansion

- Economic systems and trade networks

- Cultural and religious transformations

- Long-lasting legacy and influence on subsequent Turkic-Islamic states

Through this exploration, we aim to illuminate the Kara-Khanids' critical role as a bridge between the nomadic Turkic traditions of the steppe and the settled Islamic civilization of the Middle East and Central Asia.

|

|

|

|

Post by hun on Jul 3, 2024 22:42:17 GMT -5

Cool documentary with some great art (AI unfortunately) from the Khan's Den Youtube channel on the Rise of the Türks (Göktürks) of Mongolia. Cool...but can be a little Turko-centric at times, anyways pour yourself some fermented mare's milk and enjoy! The Celestial Turks: Origins, Culture and Rise of the Göktürk Dynasty

Description:

In the middle of the 6th century, the fate of Eurasia was about to change forever. Two brothers, Bumin and Istemi, became leaders of the Turkic Ashina, a clan of semi-nomadic steppe warriors who resided at the Altai Mountains. Like the other tribes in the area, the Ashina were known to teach their children from a young age to ride horses and the use of bow and arrow. And like the others, they were also followers of Tengri, the almighty ruler of the sky, while abiding to the Töre, the ancient traditions which regulated society. Additionally, this clan had also specialized in blacksmithing. This was a society where religious tolerance was in place, where respect among family members was expected, where ancestry was deemed holy, and in which women could become as powerful as men. But the Ashina had been forged by subjugation, being vassals of the mighty Rouran Empire. Fueled by retribution against their exploitation, and by a vision to unite the fragmented Turkic tribes, Bumin and Istemi ignited a rebellion against the Rouran ruler, called Anagui. No longer would their people be pawns in the games of these Mongolic nobles. Now, the Turks would become the architects of their OWN destiny. This is the tale of the Ashina Clan, the crucible from which emerged the Göktürk Empire — a realm that would stretch its wings from Ukraine and the Caucasus to the borders of China and Korea. In doing so, Bumin and Istemi would liberate an entire culture from the shackles of subjugation, and shape the destiny of an entire continent. They would go down in history as "the Celestial Turks".

In the first episode of the eponymous documentary series, we are going to explore the mythical origins of the Ashina tribe, its lifestyle and societal order as well as the belief system of Tengrism, the prevailing religion of all Turkic peoples. Then, we are taking a look at the situation of the tribe among its larger neighbors, their exchange with the Chinese Wei Empire, the relations to the Turkic Tiele (Tegreg) federation as well as its standing within hierarchy of the Rouran. Lastly, we will try to understand how Bumin, the successor to the unlucky Tuwu, managed to defeat the Rouran, free his peoples from bondage and establish his own Empire in a matter of only five years. Here's Episode 2 of the Celestial Turks: Expansion of the Göktürk Empire | The Celestial Turks Episode 2

Description:

In the second episode of the eponymous documentary series, we are going to explore the immediate aftermath of the foundation of the Göktürk Khaganate and take a look at the succession of rule after Bumin's death. Then, we will analyze how Bumin's brother Istemi and Bumin's sons Kara and Mukhan managed to expand the Turkic realm, doubling the Ashina Dynasty's territory within just a decade. As the Turks destroyed the Hephthalite Empire in the process, they also established cordial relations with the merchant-people of Sogdia who – in the name of the Turks – established diplomatic relations with the Byzantine Roman Empire in Europe. But this also brought the Turkic Khaganate into conflict with the mighty Sassanian dynasty in Persia.

As Istemi tried navigating through this complex tapestry of diplomacy and economic espionage and sabotage, his nephew Mukhan invaded Chinese lands for the first time. The 550s and 560s spawned the golden era of Turkic history, but has for far too long been ignored or pushed aside in mainstream media and even academia.

The time has come to put an end to this and explain to you, finally, how and why the Göktürk Empire expanded into virtually all directions and how the Turks massively influenced the fate of the Eurasian Silk Road in the long run. |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Aug 25, 2024 0:39:12 GMT -5

Keanu Reeves is Genghis Khan's Ultimate Weapon in BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B

SUMMARY SUMMARY

BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B takes fans back to the 13th century, giving a deeper look into B's life serving Genghis Khan.

Boom Studios reunites Reeves, Kindt, and Garney for a brutal showdown between B and Genghis Khan.

Historical realism adds depth to the brutal world of BRZRKR, making The Lost Book of B essential reading for fans.

Keanu Reeves’ BRZRKR returns as Genghis Khan’s ultimate weapon in the new BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B. Reeves’ soon to be iconic character is one of the most exciting comic book debuts of the past decade, shattering sales records and defying expectations. Since its conclusion, publisher Boom Studios has released special books fleshing out the BRZRKR universe, and The Lost Book of B takes fans back to the 13th century.

Boom Studios unveiled more information about BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B on their website. The book will reunite the original BRZRKR creative team of Reeves, writer Matt Kindt and artist Ron Garney. In the 13th century, B (the book’s hero) is in the employ of the notorious warlord Genghis Khan. One of Khan’s premiere soldiers, B has racked up numerous kills and victories. Yet now, B is beginning to question his loyalties, leading to a showdown of historical proportions.The book will feature a cover by Garney as well as variants by Bill Sienkiewicz and David Nakayama.

The Lost Book of B promises to be the bloodiest BRZRKR title yet. Genghis Khan was a real person, a bloodthirsty tyrant who ruled much of the known world. B was crucial to his success, but Lost Book of B looks at what happens when B questions Khan. Khan will no doubt be angry with B, which will lead to a showdown between them. Inserting historical figures into B’s story adds a layer of realism, and drives home just how long Keanu Reeves’ barbarian character has been alive. BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B will be essential reading for fans.

Source: Boom Studios

BRZRKR: The Lost Book of B is on sale August 21 from Boom Studios!

Link to previewing variant covers:

www.flickeringmyth.com/comic-book-preview-brzrkr-the-lost-book-of-b-1/

|

|

|

|

Post by hun on Sept 14, 2024 7:40:41 GMT -5

Interesting video on the ancient Bulgars: Old Great Bulgaria: Origins, Culture and Legacy of the Ancient Bulgars

Description:

The 7th century was a time of great upheaval in the Eurasian Steppe Belt. As the Turkic Khaganate, the first transcontinental Turkic Empire in history, pushed into Europe, it drove several steppe people to the west, notably the Avars. But a certain group of nomadic warriors located in modern-day Ukraine persisted in all of these arrivals: the Bulgars. These Turkic people spoke Oguric, the same Turkic dialect that was prevalent among the Huns in Europe and the White Huns in Central Asia, and are synonymous with the Onogur, a successor state to the Hunnic Empire of Attila. After the Turkic Empire’s complete disintegration, pressure from the Khazars and the newly arriving Majars made the Bulgar tribes leave their home, embarking on a journey to the southwest.

There, they founded the First Bulgar Empire and consolidated their rule in the northeast Balkans. In the following centuries, the Bulgars waged many wars against the Avars in the west, Magyars in the north, and the mighty Byzantine Empire in the east. As more nomadic Turkic peoples arrived from the steppe, including the Pechenegs and the Kipchak, the Bulgarians' identity was changing. Over time, they converted to Orthodox Christianity, and mixed with Slavic peoples, in the process adopting the Slavic language. While the political affairs of the Bulgarian Empire are well known, its pre-history – the history of Old Great Bulgaria – remains relatively obscure. We have mentioned the Bulgars many times on this channel, and will finally explore their complete history: from their roots among the Onogur people, to their traditions and culture, a possible connection to the Dulo tribe of the Göktürks, and their most prominent leaders.Here's a new video from the Khan's Den channel on the unfortunately lesser known Bulgars of the Volga: The Volga Bulgars: Muslim Turkic Warriors on the Eurasian Frontier

Desription:

Bulgar History began to take shape with the creation of Old Great Bulgaria, led by the famous Kubrat Khan. After his death, the Bulgars, an Oghur -Turkic-speaking people, split into three parts. The first group migrated westwards to the Balkans under the leadership of Asparuh. The second smaller group stayed in what is now Ukraine and became a vassal of the Turkic Khazar Empire. But a third group, consisting of several thousand people, left the area completely by heading north. After wandering along the Volga, they eventually settled in the confluence of the Volga and Kama rivers and founded their own state, known as Volga Bulgaria. It was located in the modern republic of Tatarstan in Russia.

The Volga Bulgars' interactions with several major powers, including the Khazars, the Kyivan Rus' and even ambassadors from the faraway Islamic caliphates, were characterized by a mixture of trade, diplomacy, and military conflict. From the 7th to the 13th centuries, they played a crucial role in the transfer of trade goods and culture from East to West, from South to North. The Volga Bulgars were also the first Turkic people ever to convert to Islam, although Tengrism and shamanistic beliefs remained present among the general population.

In the 13th century, their state was completely overrun by the Mongol Empire. However, their legacy survives to this day. As one of the most important but also most underrated entities along the Eurasian steppe belt, the Volga Bulgars certainly deserve our attention.

This documentary, produced and narrated by Emre-E. Yavuz for Khan's Den, aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of Volga Bulgarian culture, social structure, and diplomatic relations, shedding light on their often underappreciated role in shaping the geopolitical and cultural landscape of the medieval Eurasian steppes between European powers such as the Rus' in the west and nomadic powers like the Kipchaks in the east.

By examining contemporary chronicles, archaeological evidence, and the broader historical context, we will reconstruct the world of the Volga Bulgars and their lasting impact on Steppe, Turkic, and broader Eurasian history |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Sept 22, 2024 3:06:46 GMT -5

Fig. 1. Drone photo of Cluster 27 in northeastern Mongolia. A red circle marks the location of the excavated burial. The inset map shows the location of Cluster 27 in red and two other enclosure sites along the long wall (Clusters 23 and 24) in black. An elite grave of the pre-Mongol period, from Dornod Province, Mongolia, part 1 Fig. 1. Drone photo of Cluster 27 in northeastern Mongolia. A red circle marks the location of the excavated burial. The inset map shows the location of Cluster 27 in red and two other enclosure sites along the long wall (Clusters 23 and 24) in black. An elite grave of the pre-Mongol period, from Dornod Province, Mongolia, part 1Authors Amartuvshin Chunag a, Gideon Shelach-Lavi b, William Honeychurch c, Batdalai Byambatseren a, Orit Shamir d, Uuriintuya Munkhtur a, Daniela Wolin b, Shuzhi Wang e, Nofar Shamir f Abstract

On the Mongolian plateau, the period between the collapse of the Kitan Empire (c. 1125 CE) and the rise of the Mongol empire (1206 CE) is still poorly understood. Although events leading up to the rise of Chinggis Khan's initial Mongol state are recorded in a number of historical sources, these accounts often look backwards over decades or even centuries from the perspective of a mature empire already made. Archaeology provides one path towards a better understanding of the circumstances, people, and polities contemporaneous with the collapse of the Kitan Empire and emergence of the Jurchen Jin and Mongol states. The eastern reaches of the Mongolian plateau is a region that can speak to these events based on the material record of archaeology. The Mongol-Israeli-American Archaeological Project has surveyed and excavated along Kitan frontier ‘long-walls’ in the northeast of Mongolia since 2018. One of our fortuitous discoveries was a well-furnished burial interred within the enclosure wall of a Kitan era frontier fortress. Analysis of this grave reveals that it likely postdates the use of the fortress and provides important information about local communities, their networks, and organization during the 12th century CE.

1. Introduction

Mortuary archaeology is a powerful tool for investigating ancient pastoral nomadic societies but is most informative when combined with settlement excavation, regional information obtained by survey, and when available historical accounts (Amartuvshin, 2004; Honeychurch et al., 2007). This is particularly true for research on the Kitan-Liao (10th–12th c.) and Mongol (13th–14th c.) empires in Mongolia, periods during which political forces transformed the eastern steppe landscape introducing novel site types, settlement patterns, and diverse funerary traditions (

Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020a; Erdenebat et al., 2022). The Kitan Empire (916–1125 CE) extended into much of the eastern and central portions of Mongolia producing a complex series of frontiers further to the north and west against groups referred to somewhat generically in the histories as Zubu (Tian and Wang, 2018). As the empire began to collapse in the early 12th century, consolidation and competition marked post-frontier conditions. To the east, Manchuria, eastern Inner Mongolia, and northern China came under the control of the Jurchen state of Jin (1115–1234 CE), while on the steppe lands of Mongolia, indigenous histories introduce named political entities such as Kereit, Merkit, Tatar, Naiman and Mongol – all contending for primacy (Perlee, 1959). From this context of conflict and alliance, Chinggis Khan and the Mongols rose to power forming the Mongol state by 1206 CE (

Atwood, 2021; Biran and Kim, 2023; Fitzhugh et al., 2013).

This period during ca. 1125 to 1206 CE, between the fall of the Kitan-Liao dynasty and the rise of the Jurchen Jin state and later the Mongol Empire, is relatively obscure. Few historical documents provide concrete descriptions of the situation in Mongolia by which we can understand the social and political processes that paved the way for the rise of the Mongols (Biran and Kim, 2023; Munkh-Erdene, 2022). Archaeologically as well, very few remains are dated to this particular interval of time. Thus, any new information on issues such as the identity of people active in this region during the 12th century – their cultural, commercial, and political affiliations – is of great interest. The burial context discussed in this paper was discovered and excavated as part of the Joint Mongolian-Israeli-American Archaeological Project (Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020a,Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020b; Fung et al., 2023). Our fieldwork and research focuses on a series of long walls and associated structures, totaling more than 4000 km in extent, that were built in parts of Mongolia, Russia, and northern China sometime during the 11th to 13th centuries CE (Sun and Wang, 2009; Storozum et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2020;Kradin et al., 2019). Despite the large scale of these walls and the substantial resources invested in their construction and operation, it is unclear when exactly they were built, who built them, and what their intended function was.

Among the different wall-lines we study, the northernmost wall, located on the northeastern border region of Mongolia, South Siberia, and Inner Mongolia, is not mentioned in the relevant historical records, and until very recently, had not been studied comprehensively by historians or archaeologists. In the past few years, Mongolian and Russian archaeologists have studied this wall-line (Baasan, 2006;Kradin et al., 2019) and our team is continuing this effort using systematic survey, targeted excavations, remote sensing, the analysis of an extensive number of historical records, and paleo-climatic studies (Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020a, Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020b;Storozum et al., 2021). This line comprises a 737 km wall and ditch feature running from the Onon River basin in Mongolia (111.7° E) to the foothills of the Great Khingan Mountains (120.5° E), with a small portion protruding into southern Siberia just north of Hulun Lake (117.7° E). Along this line, forty-two clusters of structures – mostly rectangular and circular enclosures surrounded by earthen walls – are located at intervals of approximately 20–30 km spacing (Kradin et al., 2019;Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020a).

During the summer of 2018 we systematically surveyed one such cluster, labeled Cluster 27, also known as the Khar Nuur fortress (Amartuvshin et al., 2018). This site comprises a large circular enclosure (diameter 146 m) and a rectangular structure (109 × 113 m) inside of which is located another, smaller rectangular enclosure (34 × 34 m). Cluster 27 is approximately 1.4 km west of Khar Nuur lake in eastern Dornod province of Mongolia (Fig. 1). During the exploration of the smaller enclosure, fragments of bronze artifacts as well as wood, and other organic materials were exposed from the external side of the rectangular wall, near its northeastern corner. In 2021 a team of Mongolian archaeologists returned to this feature and excavated what turned out to be a well-preserved elite grave dating to 1158–1214 CE (see below for dating,Amartuvshin and Batdalai, 2021). This burial context raises important questions about the dynamics of funerary practice and social memory during a time of imperial collapse and transformation as a prior Kitan frontier zone gradually transformed into a new imperial center for the Mongol Empire (1206–1368 CE).

|

|

|

|

Post by hun on Sept 22, 2024 3:09:09 GMT -5

An elite grave of the pre-Mongol period, from Dornod Province, Mongolia, part 2

2. The grave, the deceased, and the burial assemblage

The Khar Nuur burial was dug into the outer wall of the smaller enclosure at Cluster 27 and the uppermost parts of the burial were just beginning to erode out of the surface of an extremely compact matrix of tamped-earth. Interviews with local inhabitants indicate that moderate construction work in the vicinity of this embankment had displaced and relocated surface soils and likely contributed to some mixing of deposits above the burial which, nevertheless, was a relatively shallow interment averaging only 10–15 cm below the surface of the enclosure wall. The burial contained a narrow wooden coffin made of larch (Larix sibirica) or pine (Pinus sibirica), 182 × 53 cm in size, oriented to the northeast. A well-preserved human skeleton of an adult (40–60 year old) woman in a supine position was found inside the coffin partially covered by a thin layer of tree bark (also of larch or pine,Fig. 2). Fig. 2. A plan of the excavated grave at Khar Nuur, Cluster 27 including a profile view and three elevation measurements (masl). The dotted lines show an approximate configuration of the coffin based on partial wood recovery and soil staining. Fragmentary pieces of bark originally used as a coffin cover are also shown overlying the context. The burial assemblage consists of (1) golden earrings; (2) coral and glass beads; (3) golden ornamental plaques; (4) smaller beads originally sewn into fabric; (5) a gold bracelet; (6) fragments of a bronze-framed wooden and leather object, possibly an arrow case; (7) fragments of a bronze vessel; (8) fragments of a silver cup; (9) a birch bark object provisionally identified as a traditional woman's headdress. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)Preliminary bioarchaeological assessment of the woman's skeleton reveals mild osteoarthritic changes in her joints, and conditions in the vertebral column (e.g., spondylolysis) that, taken together, suggest an active lifestyle (Schrader, 2019). Additionally, this individual lost almost all of her teeth before death, which likely resulted in difficulty chewing (see Appendix A for methods, data, and photos). The deceased woman was interred in a yellow silk robe and additional silk textiles were placed under her head. On the body and around the skeleton were found remnants of a silk garment and silk headgear, golden ornaments, diverse beads made of different materials, and other items of silver, bronze, and iron. Below we provide a description of the artifacts found in the grave followed by analytical results for wood fragments, textiles, and Bayesian modeling of radiocarbon dates.2.1. Bronze artifacts Fig. 2. A plan of the excavated grave at Khar Nuur, Cluster 27 including a profile view and three elevation measurements (masl). The dotted lines show an approximate configuration of the coffin based on partial wood recovery and soil staining. Fragmentary pieces of bark originally used as a coffin cover are also shown overlying the context. The burial assemblage consists of (1) golden earrings; (2) coral and glass beads; (3) golden ornamental plaques; (4) smaller beads originally sewn into fabric; (5) a gold bracelet; (6) fragments of a bronze-framed wooden and leather object, possibly an arrow case; (7) fragments of a bronze vessel; (8) fragments of a silver cup; (9) a birch bark object provisionally identified as a traditional woman's headdress. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)Preliminary bioarchaeological assessment of the woman's skeleton reveals mild osteoarthritic changes in her joints, and conditions in the vertebral column (e.g., spondylolysis) that, taken together, suggest an active lifestyle (Schrader, 2019). Additionally, this individual lost almost all of her teeth before death, which likely resulted in difficulty chewing (see Appendix A for methods, data, and photos). The deceased woman was interred in a yellow silk robe and additional silk textiles were placed under her head. On the body and around the skeleton were found remnants of a silk garment and silk headgear, golden ornaments, diverse beads made of different materials, and other items of silver, bronze, and iron. Below we provide a description of the artifacts found in the grave followed by analytical results for wood fragments, textiles, and Bayesian modeling of radiocarbon dates.2.1. Bronze artifacts

Parts of a small bronze vessel, originally placed next to the individual's left leg, were discovered during excavation of the burial (Fig. 2, #7). This vessel is relatively thin walled, made from bronze sheet, 0.4 mm in thickness, with the rim portions made of heavier pieces of bronze up to 6.5 mm thick. Although heavily damaged and fragmentary, it was originally 22 cm in diameter and about 15 cm high with an approximate weight of 910 g. The surface of this object is decorated with thin-line incised images and geometric figures (Fig. 3) for which comparative decorative motifs have not yet been identified on other medieval objects found in Mongolia. Several fragments of a decorated bronze-framed wooden and leather object were also found near the bronze vessel, but its identity and function are not clear. The artifactis made of 1 cm thick birch and willow wood (see below for wood identification), covered with leather, having edges framed by decorative bronze sheet (Fig. 4). One hypothesis suggests that these remains may have been a quiver or a bow and arrow case. Such artifacts have been recovered from other medieval burial assemblages, especially those of the Mongol imperial period; however, when found they are mostly, but not exclusively, found alongside male interments (Erdenebat, 2009:71–72).

Fig. 3. Remains of a decorated bronze vessel. Fig. 3. Remains of a decorated bronze vessel. Fig. 4. Fragments of a bronze-framed wooden and leather object and bronze fasteners with leather backing.2.2. Gold and silver objects Fig. 4. Fragments of a bronze-framed wooden and leather object and bronze fasteners with leather backing.2.2. Gold and silver objects

A small silver cup was found next to the left knee of the deceased. The cup was found fragmented into 26 pieces but was originally about 17 cm in diameter. The rim of the cup is slightly flattened, and its body is decorated with gilded strips and incised decorations (Fig. 5). Like the bronze vessel above, this cup seems not to have an exact matching analog, although similar silver cups have been found in Mongol medieval period burials (e.g.,Erdenebat, 2015:235). Additionally, the deceased woman was interred with a gold bracelet on her right wrist and gold earrings presumably in both ears (

Fig. 6). The bracelet is made of 0.2 cm thick gold wire and is 6.1 × 4.1 cm in size. The terminal ends of the bracelet are joined with a cast silver fastening. The manner in which the two ends of the gold wire are connected to form a bracelet is similar to a silver bracelet found in a Jurchen Jin period (1115–1234 CE) tomb from Heilongjiang province in northeast China (Heilongjiang Sheng Wenwu Kaogu Gongzuo Dui, 1977:43). The earrings are not exactly symmetrical but their shapes are very similar. One is made of 2 mm and the other of a 1.4 mm gold wire and their sizes are approximately 29 × 15 mm and 30×14 mm respectively. Also, two square golden plaques (0.7 × 1.7 cm) were attached to a thick cloth textile. Both are decorated with embossed patterns along the edges as well as in the center (Fig. 7). Two holes were pierced in each of the four corners of the ornaments to connect them to the textile backing.  Fig. 5. Fragments of a silver cup. Fig. 5. Fragments of a silver cup. Fig. 6. A gold bracelet and two gold earrings. Fig. 6. A gold bracelet and two gold earrings. Fig. 7. Two golden ornaments, one retaining its textile backing. Fig. 7. Two golden ornaments, one retaining its textile backing.

2.3. Iron items

An iron knife sheathed in a wooden case was placed under the silver cup mentioned above, which was next to the deceased's left tibia. The three parts of the knife still remaining are 14.6 cm long and 1.2 cm thick (Fig. 8). Also found within the burial chamber were several additional iron fragments in a fragmentary and oxidized state and still in need of identification, but probably representing other iron implements. Fig. 8. Fragments of an iron knife. Fig. 8. Fragments of an iron knife.

|

|

|

|

Post by hun on Sept 22, 2024 3:33:22 GMT -5

An elite grave of the pre-Mongol period, from Dornod Province, Mongolia, part 32.4. Beads

A large number of beads were found near the skeleton's neck and chest area (Fig. 2, #2 & 4) that were likely part of a necklace or pectoral decoration. Numerous smaller beads were found sewn to silk fabric, possibly the beaded remnants of a garment. Our assessment of bead types and materials are only preliminary and requires additional analysis. Of those beads that are large to medium in size, 20 are made of coral, 10 of red glass, and 5 are variously made from wound glass, gold glass, and a blue-green colored glass (Fig. 9). Interestingly, the red and blue-green colored beads probably mimic traditional eastern steppe beads made of carnelian and turquoise, both of which have substantial histories in Mongolia dating back to the Bronze Age (Kenoyer et al., 2022). Those beads of smaller size attached to fabric number in the hundreds and consist of freshwater pearls, possibly gold glass, and coral (Fig. 10).  Fig. 9. Several different varieties of glass beads. Fig. 9. Several different varieties of glass beads. Fig. 10. Beads sewn onto silk fabric.2.5. Other finds Fig. 10. Beads sewn onto silk fabric.2.5. Other finds

An object made of bark was found near the lower right leg of the deceased (Fig. 2# 9,Fig. 11). The object consists of wrapped layers of what we identified as birch bark with traces of red pigment and remnants of fabric, very likely silk. Although it is quite difficult to recognize the exact structure of this artifact, these features and materials are similar to those of a traditional woman's medieval hat or headgear, known as a bogtag malgai. Several examples of such headgear have been recovered from adult female burials of the Mongol imperial period (Erdenebat, 2006; Pozdnyakov et al., 2018).

Fig. 11. Remains of a birch bark object, likely the headgear belonging to a woman. Fig. 11. Remains of a birch bark object, likely the headgear belonging to a woman.

|

|

|

|

Post by hun on Sept 22, 2024 3:45:40 GMT -5

An elite grave of the pre-Mongol period, from Dornod Province, Mongolia, part 43. Materials analysis and dating

3.1. Analysis of wood samplesAlthough the coffin wood was badly preserved and virtually impossible to extract from the surrounding matrix without powdering the sample, our field observations suggest that it was made from planks of larch or pine with bark covering, as mentioned above. This is a preliminary assessment based on wood color and texture, pine remnants in nearby enclosure sites along the northeastern wall-line (Amartuvshin et al., 2022), and reports of larch used in some forms of Mongol period coffins (Crubezy et al., 2006:896; Erdenebat, 2015:237;Batdalai, 2024:171–77). Three wood samples from the bronze-framed wooden and leather object identified as a possible arrow case or quiver above (Fig. 2, #6), were analyzed in detail (see Appendix B). Interestingly, the samples came from three different types of wood: Salix/Populus (willow or poplar), Betula (birch), and Morus (mulberry). Birch bark was also used in the making of the object potentially identified as a medieval woman's headgear above.

Pine, larch, willow/poplar, and birch are all common tree species in forested and mixed forest-steppe areas of Mongolia. Mulberry has a northeast Asian varietal (Morus mongolica) documented in regions of Inner Mongolia, China, Japan, and Korea (Sargent, 1917:296–297), although today this varietal is not recorded as a native woody plant on the Mongolian plateau (Baasanmunkh et al., 2022). Mulberry may have been present in parts of Mongolia during the medieval era, however, the local environment around Khar Nuur lake is classic open steppe without tree cover or isolated tree stands. The local Khar Nuur environment was probably similar to today's grasslands one thousand years ago as well and this suggests that all wood in the Khar Nuur burial had non-local origins. The most likely sources for these wood types, at least today, are found in regions about 150 km north or 300 km east where the forest-steppe fringes of southern Siberia and the Greater Khingan Mountains begin.

3.2. Analysis of silk textiles

From the different textile remains found inside the grave, two bundles of 9 × 7 cm and 9.5 × 6 cm in size were initially analyzed at laboratories of the Israel Antiquities Authority in Jerusalem. Follow up analysis was carried out in Mongolia at the National University in order to study the entire textile assemblage recovered at Khar Nuur (See Appendix C for methods and full results). Fabrics from the grave are all made of silk, they do not show signs of wear or repair, and do not have evidence of having been sewn. The silken threads are reeled (filament silk) rather than spun and this kind of reeled silk is a high-quality fiber that has been identified from a number of high-status archaeological contexts in Mongolia. Most of the textiles examined are woven with a high-density plain-weave tabby technique and, notably, the silks appear to have been lengths of fabric rather than full garments. Two textiles bear gold stains, possibly from attached gold glass beads or from remains of gold strips or possibly due to gold wrapped silk threads. The silk threads analyzed are dyed blue, red, brown, and cream (Fig. 12). These samples from the Khar Nuur burial most likely originated from regions to the south in China as indicated by the material (i.e., silk), as well as the production techniques of reeled rather than spun threads.

Fig. 12. Microscopic photos of silk fabrics from the two bundles.3.3. Dating of the grave and related chronological issuesThree radiocarbon samples were taken from the uppermost layers of the exposure in 2018 – two wood samples (birch) from the provisionally identified arrow case (Fig. 2, #6) and one sheep bone recovered just above the artifact layer and attributed to the occupation of the Cluster 27 enclosure (see Appendix D for details). A sample of human bone from the burial chamber was also dated and the result agrees fairly well with the wood dates. The three AMS results for the Khar Nuur burial are provided in Table 1and the combined date range is 1158–1214 CE based on a 95% credible interval (CI). In 2019 and 2022 we conducted excavations at two other enclosure structures located to the southwest of Cluster 27 (Fig.1). The two clusters – 24 and 23 – located 50 and 73 km from Khar Nuur, are part of the same long wall system, and were likely built during the same time (Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020b). Eleven samples were taken from these two complexes providing a series of AMS dates attesting to the use-life of the two clusters (Table 2). To assess the potential time lapse between these three enclosure sites (Clusters 23, 24, and 27) and the Khar Nuur burial, we analyzed the dates from Table 1,Table 2 using Oxcal 4.4 Bayesian modeling software (see Appendix D for code and details). Unfortunately, I can't copy and paste the tables from above, you can find them at the link below: Fig. 12. Microscopic photos of silk fabrics from the two bundles.3.3. Dating of the grave and related chronological issuesThree radiocarbon samples were taken from the uppermost layers of the exposure in 2018 – two wood samples (birch) from the provisionally identified arrow case (Fig. 2, #6) and one sheep bone recovered just above the artifact layer and attributed to the occupation of the Cluster 27 enclosure (see Appendix D for details). A sample of human bone from the burial chamber was also dated and the result agrees fairly well with the wood dates. The three AMS results for the Khar Nuur burial are provided in Table 1and the combined date range is 1158–1214 CE based on a 95% credible interval (CI). In 2019 and 2022 we conducted excavations at two other enclosure structures located to the southwest of Cluster 27 (Fig.1). The two clusters – 24 and 23 – located 50 and 73 km from Khar Nuur, are part of the same long wall system, and were likely built during the same time (Shelach-Lavi et al., 2020b). Eleven samples were taken from these two complexes providing a series of AMS dates attesting to the use-life of the two clusters (Table 2). To assess the potential time lapse between these three enclosure sites (Clusters 23, 24, and 27) and the Khar Nuur burial, we analyzed the dates from Table 1,Table 2 using Oxcal 4.4 Bayesian modeling software (see Appendix D for code and details). Unfortunately, I can't copy and paste the tables from above, you can find them at the link below:

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352226724000382?via%3Dihub

Fig. 13 provides results for each model based on the available radiocarbon assays, indicating that the final occupations at Clusters 23, 24, and 27 very likely predate the construction of the burial with probabilities in the range of 87–98%. While the difference between the burial event and the last occupation of Cluster 27 ranges between 9 and 163 years based on the 95% CI, the ranges for both Cluster 23 and 24 have some potential overlap between their use-period and the burial (35 to 72 years). However, given that the bulk of probability indicates that the burial event followed these two frontier occupations (Fig. 13), our chronological evidence supports the proposition that the woman at Khar Nuur was interred after the enclosures and probably the entire wall system, were no longer in use. This interpretation is bolstered by the positioning of the grave which intruded into and potentially damaged the enclosure wall, the advanced age of the woman who likely was not involved in manning a frontier fortification, and the lack of burial artifacts having any association with the presumed function of a frontier fortress. While the Khar Nuur burial post-dates the fall of the Kitan Empire, the modeled 95% CI range slightly overlaps the historical start date for Chinggis Khan's Mongol state at 1206 CE; however, our analysis also indicates that there is only a 10.7% probability that the burial post-dates that period.

Fig. 13. Three Bayesian models comparing dates for Clusters 24, 23, and 27 to combined dates for the Khar Nuur burial. The inset figures on the right show the 95% and 68% probability regions for time intervals between the final occupation phase of each cluster and the period of burial construction and the probability that the burial predates each respective occupation. Fig. 13. Three Bayesian models comparing dates for Clusters 24, 23, and 27 to combined dates for the Khar Nuur burial. The inset figures on the right show the 95% and 68% probability regions for time intervals between the final occupation phase of each cluster and the period of burial construction and the probability that the burial predates each respective occupation.

|

|