|

|

Post by hun on Sept 22, 2024 3:53:14 GMT -5

An elite grave of the pre-Mongol period, from Dornod Province, Mongolia, part 5

4. Discussion

The 12th century CE was a time of political turmoil across the Mongolian steppe. What little documentary information we have comes from a number of historical sources that are frustratingly contradictory and obscure, but also quite fascinating when systematically compared (Atwood, 2021;Biran and Kim, 2023;Munkh-Erdene, 2011). What the historical record does offer us begins with an intriguing portrait of two centuries of Kitan hegemony over parts of the eastern steppe lands followed by the rise in Manchuria of the Jurchen Jin state (1115–1234 CE). Interactions between these imperial polities and neighboring steppe groups included resource and tax extraction, shifting alliances, cooption, and numerous military engagements (

Munkh-Erdene, 2016). Both Kitan and Jurchen Jin expansion was checked in the west, north, and northwest by groups know by the term Zubu, the exact meaning of which is debated but was clearly associated with the non-Kitan peoples of the Mongolian plateau (Liu, 2018).

The Khar Nuur burial speaks to these turbulent histories. Granted, our study focuses on a single mortuary context with limited excavation, but our results provide some insight to an understanding of Mongolian history during this roughly 80-year period between the Kitan demise (1125 CE) and Chinggis Khan's enthronement (1206 CE). The Khar Nuur burial is located in an eastern region that was inhabited by groups participating in the 12th century Mongol emergence and, prior to that, part of the Kitan and Jurchen Jin frontier zone. As a result, the region was likely embroiled in the political struggles described by the histories, involving the Tatar-Mongol conflicts, residual influence by Kitan loyalists, and Jurchen Jin struggles to stabilize its northern frontier (Atwood, 2021). A comparative perspective from mortuary archaeology helps to contextualize the broader traditions that the Khar Nuur burial practices took part in. Such comparative analysis can also provide an assessment of the affiliations and interactions engaged in by the local Khar Nuur community. Contemporaneous mortuary records available for comparison include the pre-Mongol and early Mongol burials found across the eastern and central steppe of Mongolia (11th to initial 13th c. CE) and Jurchen Jin burials from Manchuria and parts of northern China.

Jurchen Jin mortuary archaeology has consistently emphasized the most impressive burial contexts to the exclusion of the full range of practices in use during this period. These burial contexts generally have substantial underground structures comprised of several brick-built rooms and were probably associated with the uppermost elite leadership (Zhao, 2010). However, small-scale pit graves are also known, some with stone slabs but others have wooden frames or coffins, similar to the Khar Nuur burial. Graves with internal wooden structures or coffins have been found in Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, Jilin, and Shanxi provinces. They are typically 2 m in length and are relatively shallow (Zhao, 2010:24–25). Good examples are graves M2 and M3 from the Huangjiaweizi site in Zhenlai County, Jilin province. Each burial contained a single skeleton placed in a supine position with relatively few items, mainly consisting of small iron and bronze artifacts (Jilin, 1988). Only a small number of such graves have been excavated and published in China, but none of these smaller graves contain gold or silver artifacts, bronze vessels, or silks which are commonly found in the much larger Jin graves of elite individuals.

The contemporaneous mortuary archaeology of Mongolia demonstrates different patterns from those within the Jurchen Jin region. Only 25 or so burials have been reliably dated by radiocarbon or numismatics to the late Kitan through initial Mongol period and these contexts show variability, especially in burial chamber arrangement, depth of burial pits, and faunal assemblages, but generally have a common underlying structure (Erdenebat, 2009). In contrast to the Jurchen Jin mortuary record which shows significant differences in the degree of architectural investment, the Mongolian steppe record argues for the presence of portable and non-local wealth items as a primary mode of mortuary differentiation (Batdalai, 2024). This should be qualified by two important facts: first, many mortuary contexts have evidence for disruption by cultural and natural processes and, second, novel burial formats are being discovered on a fairly regular basis in Mongolia and previously unknown burials formats of the 12th century may yet be identified.

The Khar Nuur burial fits well within the contemporaneous corpus of burials known from Mongolia. General characteristics seen in a number of burials dated to this time period include interment within a burial pit, use of a wooden coffin, a northerly orientation, supine positioning, and a mixture of personal decorations, containers or vessels, as well as everyday use items (

Erdenebat, 2009; Shiraishi, 2002:19–37). Notable differences seen in the Khar Nuur context include the lack of a stone-built surface feature, the absence of pottery (although the bronze and silver vessels might have fulfilled this role), and a shallow interment depth that is an outlier although some shallow burials have been documented (Erdenebat, 2010:367–368). Some of these differences might be explained by the fact that the Khar Nuur grave was dug into an extremely compact enclosure wall. However, what stands out about the Khar Nuur burial, besides its interesting location, is the rich and varied burial goods assemblage, including unique and non-local artifacts and materials.

The artifacts recovered at Khar Nuur are distinctive and such assemblages rarely occur in burials leading up to the Mongol Empire period (Batdalai, 2024). The Khar Nuur burial might best be compared to the late 12th and early 13th century cemetery at Tavan Tolgoi located about 500 km southwest of Khar Nuur in south Sukhbaatar province (Erdenebat and Turbat, 2011). Archaeologists discovered an early Mongol period cemetery with substantial pit burials containing wooden coffins and marked by impressive stone ring features on the surface. Each burial studied revealed impressive artifact assemblages including non-local woods, silk fabrics, silver vessels and cups, and numerous examples of personal decorative items made with gold, silver, and what are likely precious worked stones. These burials have been studied extensively for aDNA, diet, and chronology and are considered to be representative of the uppermost elite or royal lineage of this region not long after their integration into the rising Mongol state (Erdenebat and Turbat, 2011; Fenner et al., 2014; Lkhagvasuren et al., 2016). These burials attest to the central importance of portable wealth for marking mortuary and likely social differences in the steppe regions of this period. Similar to the slightly less opulent Khar Nuur burial, the range of materials and craft specializations seen at Tavan Tolgoi indicate external networks that drew upon non-local products and materials from China and beyond.

5. Conclusion

In light of this historical and archaeological background, the Khar Nuur burial was likely a funerary event carried out in a region experiencing a period of post-imperial destabilization. There is a good possibility that groups inhabiting the Khar Nuur area were involved in the macro-regional political struggles of the period. From the nature of this older woman's burial, she probably belonged to a prestigious lineage of some political standing and her community was on the receiving end of wealth transfers made through networks connected to the south, east, and perhaps to the west as well. As such we might understand this woman's burial and its meaning to her respective community with regard to this greater context. Such questions touch upon archaeological treatments of local identity, social memory, landscape symbolism, and, perhaps, even political theater.

One of the most intriguing aspect of this burial is its placement within the walls of a Kitan era frontier outpost and the reasons behind that choice of location. How the Khar Nuur steppe nomads perceived the abandoned Kitan fortress, its adjacent long wall, and the fairly recent history of the neighboring Kitan Empire is difficult to know, but this funerary event elicits several hypotheses that might explain the burial and its placement. A major part of Kitan frontier strategy relied on co-opting steppe groups to manage the western and northern frontiers (Tian and Wang, 2018), plausibly including the area around Khar Nuur with its section of long wall and associated fortresses. The burial of a high-status woman of advanced age at Cluster 27 could be understood as a funerary event conducted by a local steppe community within a structure they had recently manned and so understood to be part of their own history and indigenous territory. Her burial therefore may have been perceived as affirming local identity and recent social memory.

A second hypothesis is that such enclosures assumed symbolic prestige as prominent locations on the landscape and, in this case, the Kitan enclosure was used as a funerary site for a leading member of the local community to mark her status. Still another hypothesis takes into account the political competition occurring within the greater region that may have inspired steppe groups to assert their presence, strength, and declare possession of territory. Perhaps one way to do so included opulent and public funerary events in conspicuous locales intended to draw the attention of nearby groups. These three hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, but could in fact be considered as a combined explanation for social and political processes taking place within a post-Kitan vacuum of political authority and control on the eastern steppe. As imperial authority diminished and nomadic steppe groups competed among themselves and with the distant Jin state, we might expect such combinations of social memory and identity assertion along with displays of elite prestige and power, all enacted during the poignant occasion of an older woman's burial ceremony. These factional and sub-regional dynamics would have gone hand-in-hand with the strategizing and warfare reported in the historical record, eventually ending in Mongol supremacy.CRediT authorship contribution statement

Amartuvshin Chunag: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Gideon Shelach-Lavi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. William Honeychurch: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Batdalai Byambatseren: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Orit Shamir: Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Uuriintuya Munkhtur: Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation. Daniela Wolin: Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation. Shuzhi Wang: Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation. Nofar Shamir: Formal analysis, Data curation.

Source: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352226724000382?via%3Dihub

|

|

|

|

Post by hun on Sept 30, 2024 1:15:58 GMT -5

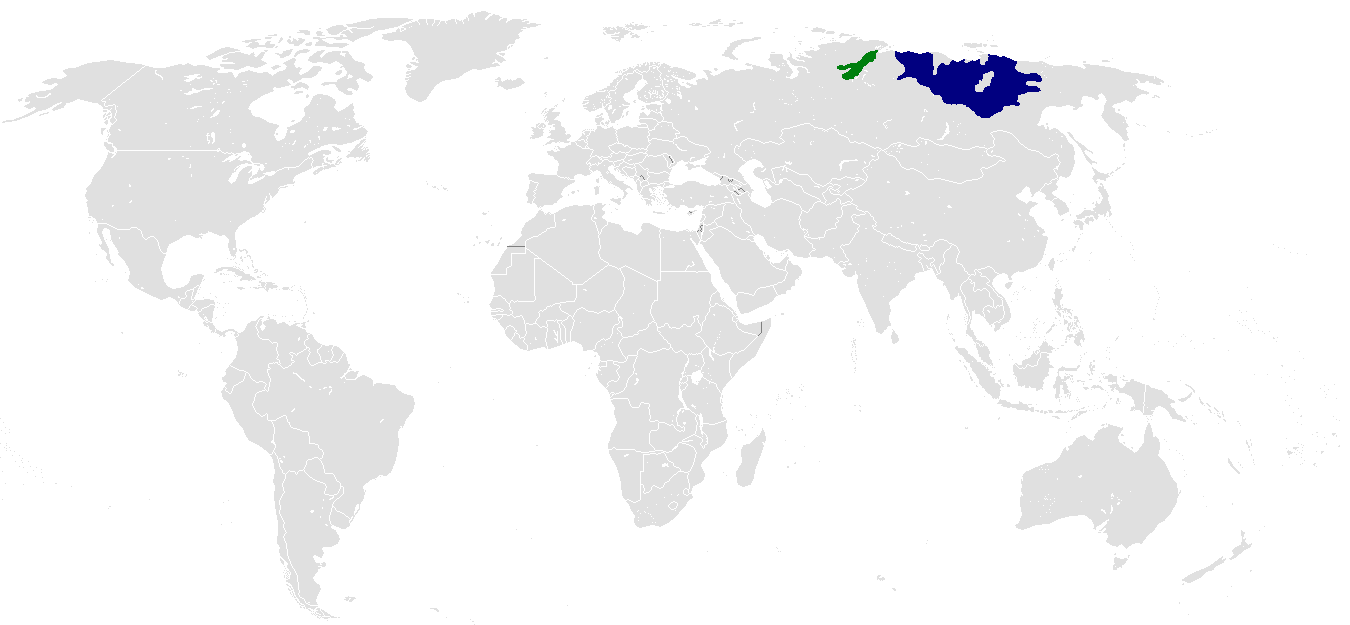

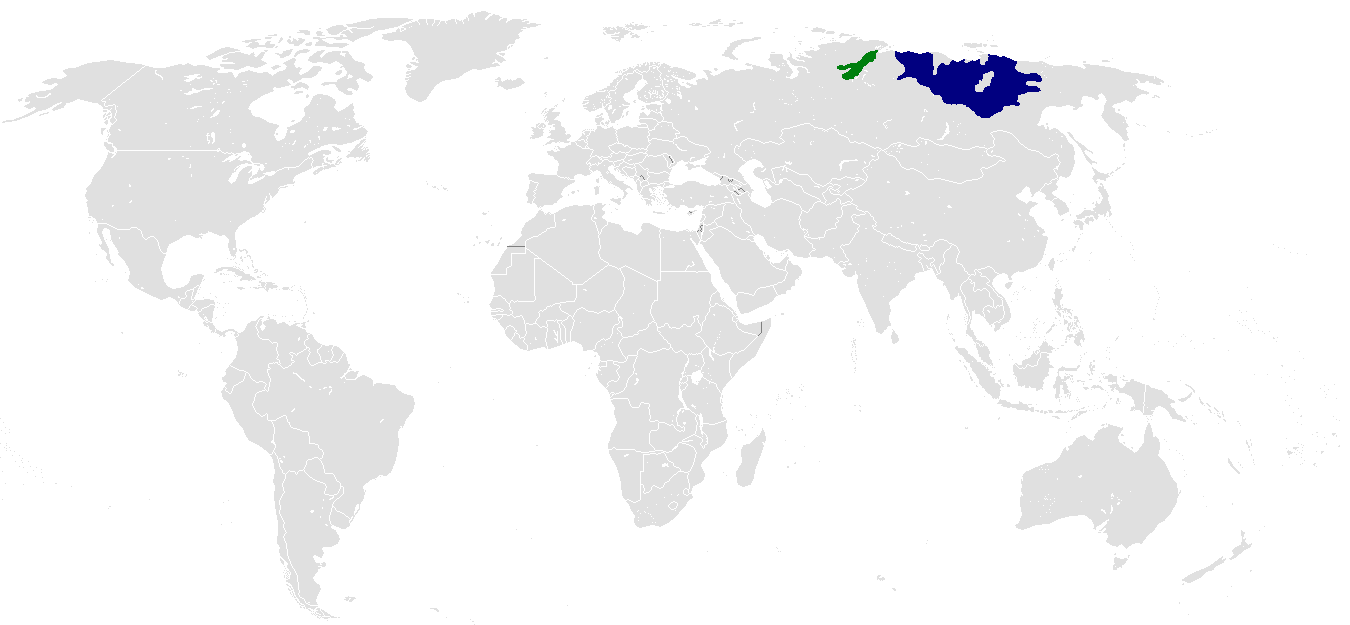

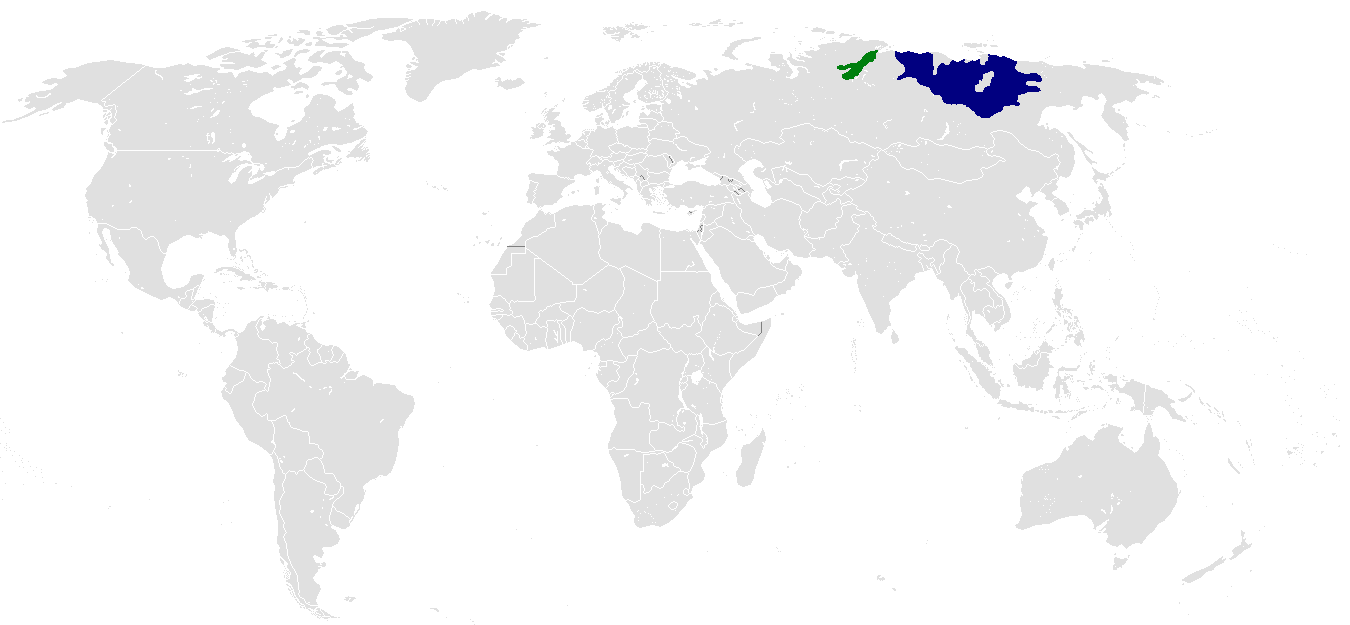

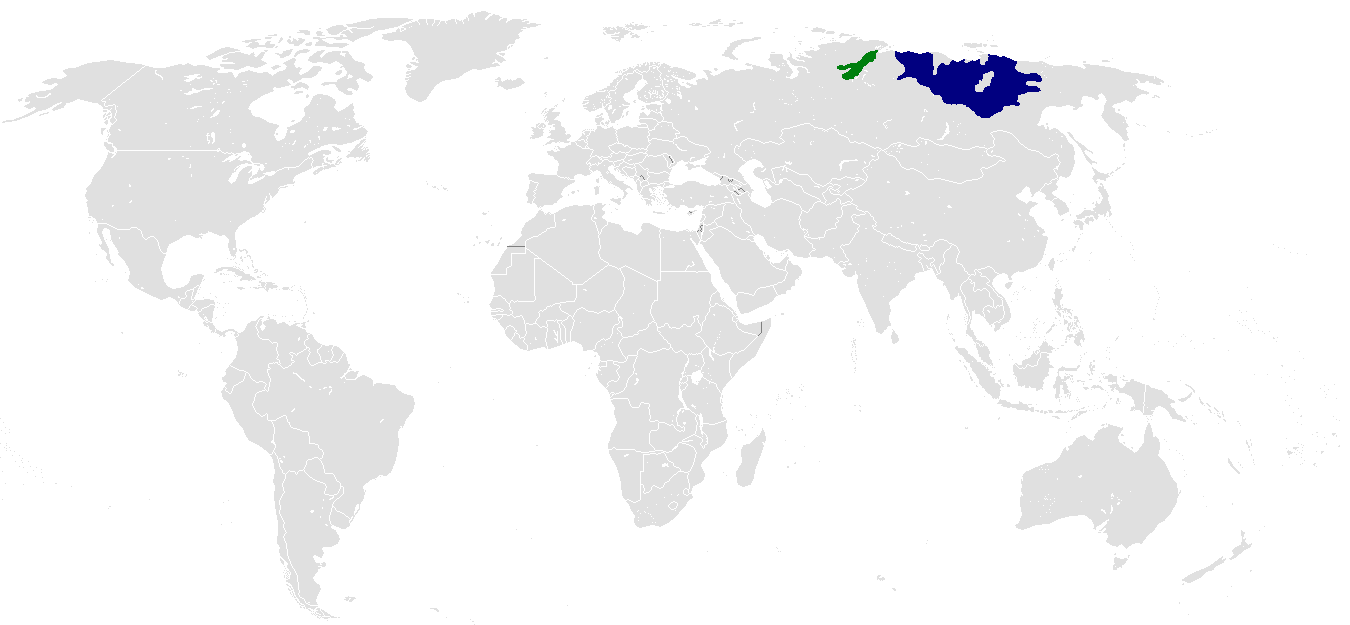

The first song on this thread in the Dolgan language of Siberia. The Dolgan are probably of Evenk descent (Tungusic), now speaking a Turkic language related to Sakha (Yakut). According to the 2010 Census there are 7,885 Dolgans, with 5,517 in Taymyrsky Dolgano-Nenetsky District, Russia. A map from Wikipedia, with the Sakha(Yakuts) in Blue and the Dolgans in Green:  Little bit about the Dolgans from wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolgansen.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolgan_language ...anyways, here the video performed by Otyken: OTYKEN - MAMMOTH (Official Music Video)DescriptionThe song was written according to the legends of the Dolgan people. The song is in the Dolgan language (a dialect of Yakut, which is common in Taimyr). The text tells about the Ice Age, mammoths and ancient people who inhabited northern Siberia. The lyrical composition is performed on ethnic musical instruments of the indigenous peoples of Siberia. In the track you can hear the sounds of cracking ice, the tread of a mammoth and the life of cave dwellers. The music immerses you in a different, pre-civilization era, in the wild, cold, prehistoric tundra. The meaning of the song includes the hypothesis of the initial settlement of America by indigenous peoples from Siberia through the Bering Strait. The main feature of the composition is the male choir of throat singing.OTYKEN band members:Producer, songwriter - Andrey Medonos Sound - Dmitry Kruzhkovsky Vocal – Azyan Drum - Hakaida Vargan (jaw harp) – Tsveta and Hara Throat Singing – Ach Igil (Morinhur) - Kunсhari Khomys (strings) – Otamay Dance – Muna and Sandro |

|

|

|

Post by kemp on Sept 30, 2024 6:55:42 GMT -5

The first song on this thread in the Dolgan language of Siberia. The Dolgan are probably of Evenk descent (Tungusic), now speaking a Turkic language related to Sakha (Yakut). According to the 2010 Census there are 7,885 Dolgans, with 5,517 in Taymyrsky Dolgano-Nenetsky District, Russia. A map from Wikipedia, with the Sakha(Yakuts) in Blue and the Dolgans in Green:  Little bit about the Dolgans from wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolgansen.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolgan_language ...anyways, here the video performed by Otyken: OTYKEN - MAMMOTH (Official Music Video)DescriptionThe song was written according to the legends of the Dolgan people. The song is in the Dolgan language (a dialect of Yakut, which is common in Taimyr). The text tells about the Ice Age, mammoths and ancient people who inhabited northern Siberia. The lyrical composition is performed on ethnic musical instruments of the indigenous peoples of Siberia. In the track you can hear the sounds of cracking ice, the tread of a mammoth and the life of cave dwellers. The music immerses you in a different, pre-civilization era, in the wild, cold, prehistoric tundra. The meaning of the song includes the hypothesis of the initial settlement of America by indigenous peoples from Siberia through the Bering Strait. The main feature of the composition is the male choir of throat singing.OTYKEN band members:Producer, songwriter - Andrey Medonos Sound - Dmitry Kruzhkovsky Vocal – Azyan Drum - Hakaida Vargan (jaw harp) – Tsveta and Hara Throat Singing – Ach Igil (Morinhur) - Kunсhari Khomys (strings) – Otamay Dance – Muna and Sandro That is really fascinating, and there is a strong thread of connection between the indigenous people of the Americas and those of Siberia, and of course we get the name Mammoth from the Siberian Manont ( or variant ), and the now extinct animals seem to appear in the folklore of the various indigenous peoples of Siberia.  Frozen baby Mammoth discovery. |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Oct 3, 2024 0:42:08 GMT -5

The first song on this thread in the Dolgan language of Siberia. The Dolgan are probably of Evenk descent (Tungusic), now speaking a Turkic language related to Sakha (Yakut). According to the 2010 Census there are 7,885 Dolgans, with 5,517 in Taymyrsky Dolgano-Nenetsky District, Russia. A map from Wikipedia, with the Sakha(Yakuts) in Blue and the Dolgans in Green:  Little bit about the Dolgans from wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolgansen.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolgan_language ...anyways, here the video performed by Otyken: OTYKEN - MAMMOTH (Official Music Video)DescriptionThe song was written according to the legends of the Dolgan people. The song is in the Dolgan language (a dialect of Yakut, which is common in Taimyr). The text tells about the Ice Age, mammoths and ancient people who inhabited northern Siberia. The lyrical composition is performed on ethnic musical instruments of the indigenous peoples of Siberia. In the track you can hear the sounds of cracking ice, the tread of a mammoth and the life of cave dwellers. The music immerses you in a different, pre-civilization era, in the wild, cold, prehistoric tundra. The meaning of the song includes the hypothesis of the initial settlement of America by indigenous peoples from Siberia through the Bering Strait. The main feature of the composition is the male choir of throat singing.OTYKEN band members:Producer, songwriter - Andrey Medonos Sound - Dmitry Kruzhkovsky Vocal – Azyan Drum - Hakaida Vargan (jaw harp) – Tsveta and Hara Throat Singing – Ach Igil (Morinhur) - Kunсhari Khomys (strings) – Otamay Dance – Muna and Sandro That is really fascinating, and there is a strong thread of connection between the indigenous people of the Americas and those of Siberia, and of course we get the name Mammoth from the Siberian Manont ( or variant ), and the now extinct animals seem to appear in the folklore of the various indigenous peoples of Siberia. Yeah, the cultural and even genetic relationship between the indigenous people of the Americas and those of Siberia, Mongolia and Central Asia is really fascinating. Here's a Map of Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup Q-M242 (Male line of descent):  The main bit in Siberia represents the area inhabited by the Yeniseian-speaking Kets, and surprisingly the bit in Central Asia is for the Turkmen, I think! Q-M242 can be found throughout the indigenous Siberian population and to a lesser degree other areas. A little more info from wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_Q-M242This one is interesting, C-M217 is sometimes associated with the Greatest Khan of the Mongols Genghis Khan - and is found predominately among the Mongols, Kazakhs and Siberians, and the indigenous Na-Dene speaking peoples of North America:  Distribution of haplogroup C2=C-M217 (YDNA), formerly C3. Here's another map of the Na-Dene speakers in North America:  Haplogroup C-M217 Wiki Page: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_C-M217 |

|

|

|

Post by kemp on Oct 4, 2024 4:52:45 GMT -5

Yeah, the cultural and even genetic relationship between the indigenous people of the Americas and those of Siberia, Mongolia and Central Asia is really fascinating. Here's a Map of Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup Q-M242 (Male line of descent):  The main bit in Siberia represents the area inhabited by the Yeniseian-speaking Kets, and surprisingly the bit in Central Asia is for the Turkmen, I think! Q-M242 can be found throughout the indigenous Siberian population and to a lesser degree other areas. A little more info from wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_Q-M242This one is interesting, C-M217 is sometimes associated with the Greatest Khan of the Mongols Genghis Khan - and is found predominately among the Mongols, Kazakhs and Siberians, and the indigenous Na-Dene speaking peoples of North America:  Distribution of haplogroup C2=C-M217 (YDNA), formerly C3. Here's another map of the Na-Dene speakers in North America:  Haplogroup C-M217 Wiki Page: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_C-M217The related Y dna frequencies between Siberian populations and especially native Americans from North America is very evident in the above charts, haplogroup Q-M242 spanning the whole of the Americas. In contrast the Turks from Anatolia probably have more Anatolian, Mediterranean and west Asian influences. |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Oct 12, 2024 11:10:03 GMT -5

A new book by Jack Weatherford on Khubilai Khan:  Emperor of the Seas: Kublai Khan and the Making of China Emperor of the Seas: Kublai Khan and the Making of China (Hardcover – 26 Sept. 2024) by Jack Weatherford (Author) "Astonishing...Brings to life a thriving - and rather civilized - empire" - The Telegraph Control the sea, and you control everything...a gripping tale of naval warfare, dynastic rivalry, and technical innovation, from the author of the classic work Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. Genghis Khan built a formidable land empire, but he never crossed the sea. Yet by the time his grandson Kublai Khan had defeated the last vestiges of the Song empire and established the Yuan dynasty in 1279, the Mongols controlled the most powerful navy in the world. How did a nomad come to conquer China and master the sea? Based on ten years of research and a lifetime of immersion in Mongol culture and tradition, Emperor of the Seas brings this little-known story vibrantly to life.

Kublai Khan is one of history's most fascinating characters. He brought Islamic mathematicians to his court, where they invented modern cartography and celestial measurement. He transformed the world's largest land mass into a unified, diverse and economically progressive empire, introducing paper money. And, after bitter early setbacks, he transformed China into an outward looking sea-faring empire.

By the end of his reign, the Chinese were building and supplying remarkable ships to transport men, grain, and weapons over vast distances, of a size and dexterity that would be inconceivable in Europe for hundreds of years. Khan had come to a brilliant realization: control the sea, and you control everything.

A master storyteller with an unparalleled grasp of Mongol sources, Jack Weatherford shows how Chinese naval hegemony changed the world forever - revolutionizing world commerce and transforming tastes as far away as England and France.

Publisher : Bloomsbury Continuum (26 Sept. 2024)

Language : English

Hardcover : 368 pages

ISBN-10 : 1399417738

ISBN-13 : 978-1399417730

Dimensions : 15.29 x 3.3 x 23.39 cm

£25/$35 Amazon Links: www.amazon.co.uk/Emperor-Seas-Kublai-Making-China/dp/1399417738/www.amazon.com/Emperor-Seas-Kublai-Making-China/dp/1399417738/ |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Oct 20, 2024 1:53:30 GMT -5

The Yuezhi: Indo-European neighbours of the Xiongnu (Huns)

We all know about The Yuetshi (Yuezhi) fisherman from 'The Devil in Iron' - but, what about the historical Yuezhi? The historical Yuezhi were the South-Western neighbours of the Xiongnu. To the east of the Xiongnu roamed the Donghu (Eastern Barbarians) Hu was a general term the Chinese used for barbarians.  map from wikipedia. The Unusual thing about the Yuezhi is that they probably spoke a Tocharian language, which is believed to be closer to the western Indo-European languages. The king of the Xiongnu, Modu Chanyu (reigned 209BC-174BC) defeated the Yuezhi - the job was finished off by Modu's son, he made a made a drinking cup out of the skull of the Yuezhi king. This set in motion the great migration of the Yuezhi into the heart of Central Asia. The rise of Xiongnu power, was probably the beginning of the expansion of the Altaic languages beyond Mongolia, Manchuria, Northern China and Siberia. A book I'm keen on picking up one day.  The Yuezhi. Origin, Migration and the Conquest of Northern Bactria The Yuezhi. Origin, Migration and the Conquest of Northern Bactria by C. Benjamin This book provides a detailed narrative history of the dynasty and confederation of the Yuezhi, whose migration from western China to the northern border of present-day Afghanistan resulted ultimately in the creation of the Kushan Empire. Although the Yuezhi have long been recognised as the probable ancestors of the Kushans, they have generally only been considered as a prelude to the principal subject of Kushan history, rather than as a significant and influential people in their own right. The evidence seemed limited and ambiguous, but is actually surprisingly extensive and detailed and certainly sufficient to compile a comprehensive chronological political history of the Yuezhi during the first millennium BCE. The book analyses textual, numismatic and archaeological evidence in an attempt to explain the probable origin of the Yuezhi, their relationship with several Chinese dynasties, their eventual military defeat and expulsion from the Gansu by the Xiongnu, their migration through the Ili Valley, Ferghana and Sogdia to northern Bactria, and their role in the conquest of the former Greco-Bactria state. All of these events were bound up with broader cultural and political developments in ancient Central Asia and show the extraordinary interconnectedness of the Eurasian historical processes. The domino-effect of the migration of the Yuezhi led to significant changes in the broader Eurasian polity.Publisher : Brepols Publishers; 1st edition (28 Feb. 2007) Language : English Paperback : 263 pages Amazon Link: www.amazon.co.uk/Yuezhi-Migration-Conquest-Northern-Bactria/dp/250352429X/ Another book by Craig Benjamin.  Craig Benjamin, Empires of Ancient Eurasia: The First Silk Roads Era, 100 BCE – 250 CE, Cambridge University Press, 2018. Craig Benjamin, Empires of Ancient Eurasia: The First Silk Roads Era, 100 BCE – 250 CE, Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Description:

The Silk Roads are the symbol of the interconnectedness of ancient Eurasian civilizations. Using challenging land and maritime routes, merchants and adventurers, diplomats and missionaries, sailors and soldiers, and camels, horses and ships, carried their commodities, ideas, languages and pathogens enormous distances across Eurasia. The result was an underlying unity that traveled the length of the routes, and which is preserved to this day, expressed in common technologies, artistic styles, cultures and religions, and even disease and immunity patterns. In words and images, Craig Benjamin explores the processes that allowed for the comingling of so many goods, ideas, and diseases around a geographical hub deep in central Eurasia. He argues that the first Silk Roads era was the catalyst for an extraordinary increase in the complexity of human relationships and collective learning, a complexity that helped drive our species inexorably along a path towards modernity.

The first accessible single-volume history of all of ancient Eurasia, offering an account of the major sedentary and nomadic states and empires of the region

Conceptualizes the Silk Roads within big history, world-systems, and ancient globalizations to connect history and theory

Offers a fresh approach to understanding historical developments in the ancient world.Let's have butcher's at the Contents: Introduction

1. Pastoral nomads and the empires of the Steppe

2. Early China: prelude to the silk roads

3. Zhang Qian and Han expansion into Central Asia

4. The early Han dynasty and the Eastern Silk Roads

5. Rome and the Western Silk Roads

6. The Parthian Empire and the Silk Roads

7. The Kushan Empire: at the crossroads of ancient Eurasia

8. Maritime routes of the first Silk Roads era

9. Collapse of Empires and the decline of the first Silk Roads era

Conclusion.

Publisher : Cambridge University Press (3 May 2018) Language : English Paperback : 316 page Amazon Link: www.amazon.co.uk/Empires-Ancient-Eurasia-Approaches-History/dp/1107535433/Video by Kings & Generals YouTube channel concerning the Yuezhi Kushan Empire of Central Asia: Yuezhi Migration and Kushan Empire - Nomads DOCUMENTARY

Kings and Generals' historical animated documentary series on the history of Ancient Civilizations and Nomadic Cultures continues with a video on the Yuezhi - the nomadic people who were neighbors of the Qin and Han Chinese dynasties and the Xiongnu and Wusun nomads, but were driven to Central Asia. From here the Yuezhi created their Kusha Empire in Central Asia and North India. This migration played a crucial role in the history of India, Iran, Central Asia and Buddhism. |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Oct 26, 2024 0:51:01 GMT -5

Interesting look at the 'Golden Man/Woman' of Kazakhstan. Probably dating sometime between the 5th to the 3rd century BC and of Saka (Eastern Scythian) origin. The Turkic translation of the inscription on the silver bowl in the video does not seem right to me, the translation is too close to modern Turkish. The Hungarian scholar János Harmatta, probably got closer with his decipherment: the language spoken at this time, in this area, was probably an Eastern Iranic Language. Anyways, have a butcher's at the video to find out a little bit more about the Golden Man or Woman of the Issyk Kurgan: Mystery of the Issyk Golden Prince in Kazakhstan | Secret of the Steppes Episode 1

In the sun-baked steppes of Kazakhstan, a 2,500-year-old burial mound holds a secret that challenges our understanding of ancient Turkic culture. The Issyk Golden Man, adorned with thousands of gold ornaments, raises more questions than answers. Who was this young ruler? Why was he buried with such opulence? Was "he" perhaps a "she"? And what does his mysterious death reveal about power dynamics in the early steppe societies?

Let's explore how this gilded mystery challenges our understanding of early nomadic societies and their forgotten rulers, and therefore set off a new series on Khan's Den: Secrets of the Steppes.

Amazon Link: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Issyk_kurgan |

|

|

|

Post by kemp on Oct 26, 2024 5:48:18 GMT -5

Interesting look at the 'Golden Man/Woman' of Kazakhstan. Probably dating sometime between the 5th to the 3rd century BC and of Saka (Eastern Scythian) origin. The Turkic translation of the inscription on the silver bowl in the video does not seem right to me, the translation is too close to modern Turkish. The Hungarian scholar János Harmatta, probably got closer with his decipherment: the language spoken at this time, in this area, was probably an Eastern Iranic Language. Anyways, have a butcher's at the video to find out a little bit more about the Golden Man or Woman of the Issyk Kurgan: Mystery of the Issyk Golden Prince in Kazakhstan | Secret of the Steppes Episode 1

In the sun-baked steppes of Kazakhstan, a 2,500-year-old burial mound holds a secret that challenges our understanding of ancient Turkic culture. The Issyk Golden Man, adorned with thousands of gold ornaments, raises more questions than answers. Who was this young ruler? Why was he buried with such opulence? Was "he" perhaps a "she"? And what does his mysterious death reveal about power dynamics in the early steppe societies?

Let's explore how this gilded mystery challenges our understanding of early nomadic societies and their forgotten rulers, and therefore set off a new series on Khan's Den: Secrets of the Steppes.

Amazon Link: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Issyk_kurganI wondered about the relationship between the east Iranian peoples and early Turks, notably in relation to the Kurgan burial mounds in China, take for instance the Donghu, they seem to be an amalgamation of various influences over a certain period of time, that is Scythians, Mongols and Turks, but perhaps predominantly Mongolian. I think the history of these people, also their interactions with one another is older than we think.  |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Nov 3, 2024 13:54:21 GMT -5

Interesting look at the 'Golden Man/Woman' of Kazakhstan. Probably dating sometime between the 5th to the 3rd century BC and of Saka (Eastern Scythian) origin. The Turkic translation of the inscription on the silver bowl in the video does not seem right to me, the translation is too close to modern Turkish. The Hungarian scholar János Harmatta, probably got closer with his decipherment: the language spoken at this time, in this area, was probably an Eastern Iranic Language. Anyways, have a butcher's at the video to find out a little bit more about the Golden Man or Woman of the Issyk Kurgan: Mystery of the Issyk Golden Prince in Kazakhstan | Secret of the Steppes Episode 1

In the sun-baked steppes of Kazakhstan, a 2,500-year-old burial mound holds a secret that challenges our understanding of ancient Turkic culture. The Issyk Golden Man, adorned with thousands of gold ornaments, raises more questions than answers. Who was this young ruler? Why was he buried with such opulence? Was "he" perhaps a "she"? And what does his mysterious death reveal about power dynamics in the early steppe societies?

Let's explore how this gilded mystery challenges our understanding of early nomadic societies and their forgotten rulers, and therefore set off a new series on Khan's Den: Secrets of the Steppes.

Amazon Link: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Issyk_kurganI wondered about the relationship between the east Iranian peoples and early Turks, notably in relation to the Kurgan burial mounds in China, take for instance the Donghu, they seem to be an amalgamation of various influences over a certain period of time, that is Scythians, Mongols and Turks, but perhaps predominantly Mongolian. I think the history of these people, also their interactions with one another is older than we think.  Yeah, the Donghu (Eastern Hu in Chinese) were pretty interesting, they were the eastern neighbours of the Xiongnu (Huns), some tribes spoke Turkic, I think the Mongolian language, was probably, the prominent language of the Xianbei branch of the Donghu. The ruling Tabgach clan seem to have spoken a Turkic and/or Mongolian language according to some translations (The Tabgach adopted the Chinese script for their language). I gotta feeling, the Yeniseian and Uralic languages were also in the mix, probably playing an integral part, at times among the Iranic and Altaic peoples in the past. I read some of the translations of the Tabgach years ago in the book below, the language seems to be more Mongolian than Turkic, many of the words were shared by both languages but some were only found in the Mongolic languages:  Books of the Mongolian Nomads: More Than Eight Centuries of Writing Mongolian (Uralic and Altaic Studies) Books of the Mongolian Nomads: More Than Eight Centuries of Writing Mongolian (Uralic and Altaic Studies) Hardcover – 30 Sept. 2005 by Gyorgy Kara (Author), John R. Krueger (Translator) The fascinating story of the visualized languages, alphabets, and other writing systems, hand-written and block-printed books of the Mongols, Kalmyks, Buryats, and other Mongolian nations is outlined in this study by one of the world's preeminent scholars of the region. The mostly nomadic peoples of the Mongolian language family have a long history of letters. The Khitans had two writing systems, both of Chinese inspiration and still not fully deciphered. In Chinggis Khan's world empire and in the later Mongolian societies, a number of various alphabets of Mediterranean and Indo-Tibetan origin were used alternatively, according to the needs and caprices of faith and political power. Similarly, the contents and shapes of books and related monuments, the loose "palm leaves," the accordion-style and the double-leaved "notebook" forms, scrolls, stone inscriptions, and seals reflect the complex cultural history of the Mongols of Mongolia, China, and European and Asiatic Russia.Amazon Link: www.amazon.co.uk/Mongolian-Nomads-Uralic-Altaic-Studies/dp/0933070527/ |

|

|

|

Post by kemp on Nov 3, 2024 19:18:57 GMT -5

Yeah, the Donghu (Eastern Hu in Chinese) were pretty interesting, they were the eastern neighbours of the Xiongnu (Huns), some tribes spoke Turkic, I think the Mongolian language, was probably, the prominent language of the Xianbei branch of the Donghu. The ruling Tabgach clan seem to have spoken a Turkic and/or Mongolian language according to some translations (The Tabgach adopted the Chinese script for their language). I gotta feeling, the Yeniseian and Uralic languages were also in the mix, probably playing an integral part, at times among the Iranic and Altaic peoples in the past. I read some of the translations of the Tabgach years ago in the book below, the language seems to be more Mongolian than Turkic, many of the words were shared by both languages but some were only found in the Mongolic languages:  Books of the Mongolian Nomads: More Than Eight Centuries of Writing Mongolian (Uralic and Altaic Studies) Books of the Mongolian Nomads: More Than Eight Centuries of Writing Mongolian (Uralic and Altaic Studies) Hardcover – 30 Sept. 2005 by Gyorgy Kara (Author), John R. Krueger (Translator) The fascinating story of the visualized languages, alphabets, and other writing systems, hand-written and block-printed books of the Mongols, Kalmyks, Buryats, and other Mongolian nations is outlined in this study by one of the world's preeminent scholars of the region. The mostly nomadic peoples of the Mongolian language family have a long history of letters. The Khitans had two writing systems, both of Chinese inspiration and still not fully deciphered. In Chinggis Khan's world empire and in the later Mongolian societies, a number of various alphabets of Mediterranean and Indo-Tibetan origin were used alternatively, according to the needs and caprices of faith and political power. Similarly, the contents and shapes of books and related monuments, the loose "palm leaves," the accordion-style and the double-leaved "notebook" forms, scrolls, stone inscriptions, and seals reflect the complex cultural history of the Mongols of Mongolia, China, and European and Asiatic Russia.Amazon Link: www.amazon.co.uk/Mongolian-Nomads-Uralic-Altaic-Studies/dp/0933070527/I'm still trying to wrap my head around all these steppe language families. That study might go some way to helping out people like me who are still looking at this in layman terms, but it really does frustrate easy classification. Years ago, I would view the Khitans as a kind of proto Chinese people, but I understand now that they are probably more of a proto Mongolian sub section that came to dominate China, that is culture and language, more than a thousand years ago, the Liao dynasty, but this attests to the Mongolian influence over China, and from what I understand Mongolian is still one of the country's official languages, but so is English by way of Hong Kong. The exact Khitan language or dialect of the Mongolian family died out in the 1200's, language family maybe Para Mongolic or even Serbi Mongolic ?? The Serbi is curious, but a construction of the historical ethnonym Xianbei, an ancient nomadic people that at one resided in the eastern Eurasian steppes, Chinese scribes transcribing Middle Persian Ser ( lion), also Sanskrit. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/XianbeiThe Ser word disambiguation seems to spread over a number of Eurasian peoples, the old relationship between Mongolian, Indo European/Aryan and Turkic language families....but some purely accidental in translation. I am no linguist, but I hardly think there is a connection between Australia and Austria  Now where is that headache tablet. |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Nov 3, 2024 23:43:50 GMT -5

Yeah, the Donghu (Eastern Hu in Chinese) were pretty interesting, they were the eastern neighbours of the Xiongnu (Huns), some tribes spoke Turkic, I think the Mongolian language, was probably, the prominent language of the Xianbei branch of the Donghu. The ruling Tabgach clan seem to have spoken a Turkic and/or Mongolian language according to some translations (The Tabgach adopted the Chinese script for their language). I gotta feeling, the Yeniseian and Uralic languages were also in the mix, probably playing an integral part, at times among the Iranic and Altaic peoples in the past. I read some of the translations of the Tabgach years ago in the book below, the language seems to be more Mongolian than Turkic, many of the words were shared by both languages but some were only found in the Mongolic languages:  Books of the Mongolian Nomads: More Than Eight Centuries of Writing Mongolian (Uralic and Altaic Studies) Books of the Mongolian Nomads: More Than Eight Centuries of Writing Mongolian (Uralic and Altaic Studies) Hardcover – 30 Sept. 2005 by Gyorgy Kara (Author), John R. Krueger (Translator) The fascinating story of the visualized languages, alphabets, and other writing systems, hand-written and block-printed books of the Mongols, Kalmyks, Buryats, and other Mongolian nations is outlined in this study by one of the world's preeminent scholars of the region. The mostly nomadic peoples of the Mongolian language family have a long history of letters. The Khitans had two writing systems, both of Chinese inspiration and still not fully deciphered. In Chinggis Khan's world empire and in the later Mongolian societies, a number of various alphabets of Mediterranean and Indo-Tibetan origin were used alternatively, according to the needs and caprices of faith and political power. Similarly, the contents and shapes of books and related monuments, the loose "palm leaves," the accordion-style and the double-leaved "notebook" forms, scrolls, stone inscriptions, and seals reflect the complex cultural history of the Mongols of Mongolia, China, and European and Asiatic Russia.Amazon Link: www.amazon.co.uk/Mongolian-Nomads-Uralic-Altaic-Studies/dp/0933070527/I'm still trying to wrap my head around all these steppe language families. That study might go some way to helping out people like me who are still looking at this in layman terms, but it really does frustrate easy classification. Years ago, I would view the Khitans as a kind of proto Chinese people, but I understand now that they are probably more of a proto Mongolian sub section that came to dominate China, that is culture and language, more than a thousand years ago, the Liao dynasty, but this attests to the Mongolian influence over China, and from what I understand Mongolian is still one of the country's official languages, but so is English by way of Hong Kong. The exact Khitan language or dialect of the Mongolian family died out in the 1200's, language family maybe Para Mongolic or even Serbi Mongolic ?? The Serbi is curious, but a construction of the historical ethnonym Xianbei, an ancient nomadic people that at one resided in the eastern Eurasian steppes, Chinese scribes transcribing Middle Persian Ser ( lion), also Sanskrit. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/XianbeiThe Ser word disambiguation seems to spread over a number of Eurasian peoples, the old relationship between Mongolian, Indo European/Aryan and Turkic language families....but some purely accidental in translation. I am no linguist, but I hardly think there is a connection between Australia and Austria  Now where is that headache tablet. ri Khan It is difficult, especially when we rely on Chinese sources for the names of Leaders and tribes of the steppe. Serbi is a recent reconstruction the name of the Xianbei, by Shimunek, I think. The Tuoba, known as Tabgach in the Turkic Inscriptions is obvious, I guess. We also know the personal/Tabgach name of the Emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei (423-452), he was known as Büri Khan (translates as Wolf Khan in Turkic, probably a cognate found in Mongolian, as Börte: the 1st wife of Genghis, Börte Chino, as grey, or greyish-blue wolf). In the live action Mulan movie Jason Scott Lee portrayed Bori Khan, not as the emperor of China, but as the Khan of the Rouran!  Even the name Rouran is impossible in any Altaic language (no Turkic/Mongolian name can begin with an R or L), that is until the recent introduction of loanwords from other languages. The same goes for the Avars - the ancient Turkic and Mongolian peoples did not use the letters F, V and W. So, the Avars probably sounded something more like Apars, or the name could've been a loan word. The recently deciphered Göktürk inscriptions of the first empire are in Mongolian, not Turkic. Could the founders of the Göktürk be of Mongolic origin? |

|

|

|

Post by kemp on Nov 4, 2024 3:48:54 GMT -5

It is difficult, especially when we rely on Chinese sources for the names of Leaders and tribes of the steppe. Serbi is a recent reconstruction the name of the Xianbei, by Shimunek, I think. The Tuoba, known as Tabgach in the Turkic Inscriptions is obvious, I guess. We also know the personal/Tabgach name of the Emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei (423-452), he was known as Büri Khan (translates as Wolf Khan in Turkic, probably a cognate found in Mongolian, as Börte: the 1st wife of Genghis, Börte Chino, as grey, or greyish-blue wolf). In the live action Mulan movie Jason Scott Lee portrayed Bori Khan, not as the emperor of China, but as the Khan of the Rouran!  Even the name Rouran is impossible in any Altaic language (no Turkic/Mongolian name can begin with an R or L), that is until the recent introduction of loanwords from other languages. The same goes for the Avars - the ancient Turkic and Mongolian peoples did not use the letters F, V and W. So, the Avars probably sounded something more like Apars, or the name could've been a loan word. The recently deciphered Göktürk inscriptions of the first empire are in Mongolian, not Turkic. Could the founders of the Göktürk be of Mongolic origin? I always thought that the Gokturks were Turks, but not even that is so simple, as you just highlighted above by way of the Gokturk inscriptions. Serves me right for relying too much on those Osprey Publishing Warrior series books I used to collect. Of course both the Turks and Mongolians have a very close relationship from the earliest of times which may account for the difficulties in trying to seperate the strands. Didn't the Gokturks originate from the Ashina tribe ( not to be confused with the Japanese Ashina clan ), and then we start to involve maybe the Tocharians and eastern Iranian peoples. Interesting that the Grey wolf, the sacred animal in Turkish mythology ( also Mongolian ) is translated as 'Bori' in the old Turkic, and also figures as the wolf Ashina. 'The gray wolf, known as “bozkurt” in Turkish and “boskord” and “pusgurt” in other languages, holds a prominent place in Turkish, Mongolian and Altai mythologies. This sacred animal, also referred to as “bortecine,” “gokkurt,” “gokboru” or “kokboru” among Turks, symbolizes a variety of attributes, including warfare, freedom, nature, wisdom and guidance. The gray wolf became a national symbol for Turks primarily due to its pivotal role in the Ergenekon Epic. Legend tells of the Turks being imprisoned for generations within Ergenekon. A mighty blacksmith finally broke them free by melting the rock with fire. Asena, a sacred she-wolf, and Bortecine, a gray wolf, then guided them to safety. This epic portrays the wolf as a wise leader and protector, appearing whenever the Turkish nation faces hardship' www.turkiyetoday.com/culture/grey-wolf-sacred-symbol-in-turkish-and-roman-mythology-26154/ A giant statue of the sacred “gokkurt” (wolf), in Kazakhstan. (Photo by Habererk) |

|

|

|

Post by hun on Nov 9, 2024 1:26:16 GMT -5

It is difficult, especially when we rely on Chinese sources for the names of Leaders and tribes of the steppe. Serbi is a recent reconstruction the name of the Xianbei, by Shimunek, I think. The Tuoba, known as Tabgach in the Turkic Inscriptions is obvious, I guess. We also know the personal/Tabgach name of the Emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei (423-452), he was known as Büri Khan (translates as Wolf Khan in Turkic, probably a cognate found in Mongolian, as Börte: the 1st wife of Genghis, Börte Chino, as grey, or greyish-blue wolf). In the live action Mulan movie Jason Scott Lee portrayed Bori Khan, not as the emperor of China, but as the Khan of the Rouran!  Even the name Rouran is impossible in any Altaic language (no Turkic/Mongolian name can begin with an R or L), that is until the recent introduction of loanwords from other languages. The same goes for the Avars - the ancient Turkic and Mongolian peoples did not use the letters F, V and W. So, the Avars probably sounded something more like Apars, or the name could've been a loan word. The recently deciphered Göktürk inscriptions of the first empire are in Mongolian, not Turkic. Could the founders of the Göktürk be of Mongolic origin? I always thought that the Gokturks were Turks, but not even that is so simple, as you just highlighted above by way of the Gokturk inscriptions. Serves me right for relying too much on those Osprey Publishing Warrior series books I used to collect. Of course both the Turks and Mongolians have a very close relationship from the earliest of times which may account for the difficulties in trying to seperate the strands. Didn't the Gokturks originate from the Ashina tribe ( not to be confused with the Japanese Ashina clan ), and then we start to involve maybe the Tocharians and eastern Iranian peoples. Interesting that the Grey wolf, the sacred animal in Turkish mythology ( also Mongolian ) is translated as 'Bori' in the old Turkic, and also figures as the wolf Ashina. 'The gray wolf, known as “bozkurt” in Turkish and “boskord” and “pusgurt” in other languages, holds a prominent place in Turkish, Mongolian and Altai mythologies. This sacred animal, also referred to as “bortecine,” “gokkurt,” “gokboru” or “kokboru” among Turks, symbolizes a variety of attributes, including warfare, freedom, nature, wisdom and guidance. The gray wolf became a national symbol for Turks primarily due to its pivotal role in the Ergenekon Epic. Legend tells of the Turks being imprisoned for generations within Ergenekon. A mighty blacksmith finally broke them free by melting the rock with fire. Asena, a sacred she-wolf, and Bortecine, a gray wolf, then guided them to safety. This epic portrays the wolf as a wise leader and protector, appearing whenever the Turkish nation faces hardship' www.turkiyetoday.com/culture/grey-wolf-sacred-symbol-in-turkish-and-roman-mythology-26154/ A giant statue of the sacred “gokkurt” (wolf), in Kazakhstan. (Photo by Habererk) Interestingly, the Ergenekon Epic was an origin story of the Mongols, (not including the Keriats, Naiman's, Merkits, Oirats, Tatars and other Turco-Mongolian tribes) originally found in the Compendium of Chronicles by Rashid-al-Din. Ergenekon is not mentioned in the Secret History of the Mongols. The origin of the Oghuz tribes can also be found in the Compendium of Chronicles. In this version the baby Oghuz refuses his mother's milk unless she converts to Islam. In the pagan Uyghur version of Oghuz Kaghan he wants to drink alcohol instead of milk, I like him already - there is also a wolf that guides the hero. Modern Turkish Nationalists have combined Ergenekon with the above epics and the origin of the Göktürks found in the Chinese sources, to add further confusion there's more than one origin in the Chinese sources! The Ashina are not mentioned in the Turkic/Mongolian inscriptions in Mongolia and is a Chinese rendition of the name. Böri Khan of the Northern Wei defeated the Hunnic (Xiongnu) Dynasty of the Northern Liang in 439AD. This led to the migration of the ancestors of the Göktürks, around 500 Ashina tribesmen from Gansu in China to Mongolia. By Crom & Tengri, I loved those Osprey Publishing Warrior series. Some great art in them books too. |

|

|

|

Post by kemp on Nov 12, 2024 0:18:22 GMT -5

The more I look into it, and going from the information presented by sources such as you on this thread, not to mention the links and other material, I'm convinced that the Turks and Mongols did not exist in a cultural vacuum, but have borrowed from each other almost after the Turks first came on the scene in the Altai and Siberian regions, the mingling of people and cultures in South Siberia, so the association of the first Turkic Khaganate with the Epic of Ergenekon makes sense, even if the myth was originally Mongolian before being incorporated by the Turks. Also interesting is the early Turkic and Iranian interactions, probably starting with the aforementioned first Turkic Khaganate, but perhaps even earlier in Scytho Siberian areas, also in what is now Khazakhstan by way of the Scythian Saka, although early Scythians and Sarmatians had an Indo Aryan/Iranian origin, but that is also true of the Persians. Scythian Saka Pyramid some 3400 years old.  |

|